As you sit back and savour every last drop of that creamy chardonnay from the Niagara Peninsula, that pinot blanc dripping in fruit from the Okanagan Valley or that silky smooth Canadian pinot noir, save a bit to toast those who dared to dream that it was possible to make world class wines in this country.

It was a dream that was 150 years in the making but only realized in the last 30 years or so thanks to a few visionaries who saw the potential for a Canadian wine industry and turned their dogged determination into what we enjoy today — a vast wonderland of fabulous table wines, fruit wines, ciders and our famous ice wines made coast to coast in every style and grape varietal imaginable.

•••

Ernest Hemingway was fond of saying that “wine is the most civilized thing in the world.” But one wonders if Hemingway, the brilliant U.S. writer who loved his wine, was referring to the wines of the day in Canada. If he was, we would be correct to question his palate.

Ernest Hemingway was fond of saying that “wine is the most civilized thing in the world.” But one wonders if Hemingway, the brilliant U.S. writer who loved his wine, was referring to the wines of the day in Canada. If he was, we would be correct to question his palate.

Canadian wine, prior to the 1970s, was anything but “civilized.” It was, with a few exceptions, horrid swill, a combination of labrusca and other native grapes that grew vigorously but produced barely drinkable wines.

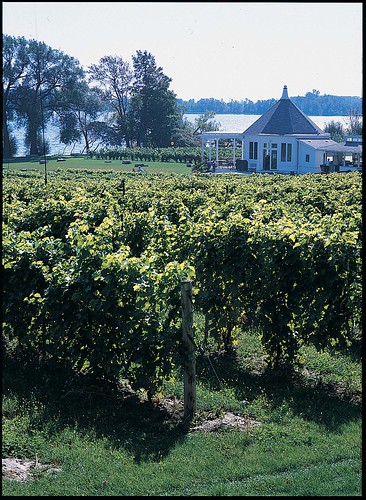

For most of the 150 years that Canadians have been making wine (the first commercial winemaking operation in Canada began in 1866 on Pelee Island in southern Ontario), it is only within the last few decades that our wines have gone from domestic obscurity to international superstar, able to compete with some of the finest wines in the world.

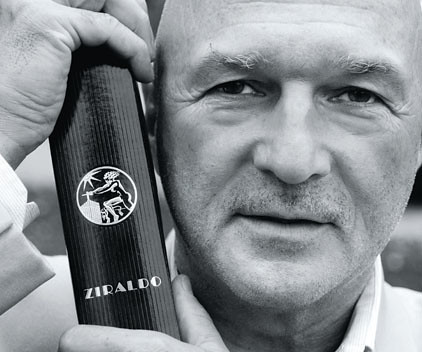

Much of the credit for the booming industry today goes to a couple of men — Donald Ziraldo and Harry McWatters. And even though they toiled 4,200 kilometres apart, Ziraldo in Niagara and McWatters in the Okanagan, their goals were the same: to make 100% Canadian wines that would turn heads the world over.

In the early 1970s, Ziraldo said, Niagara wine producers were making “Canadian” wines with at least some labrusca grapes in the blend and imported grape juice from other countries. There were no rules that guided wineries and therefore no incentives to try planting the hard-to-grow vinifera varietals (noble European grapes that are common today such as chardonnay, riesling, cabernet sauvignon and merlot) that worked well in other wine regions of the world.

After visiting relatives in Italy in the early 1970s, Ziraldo came home to Niagara and began experimenting with vinifera at his nursery. He and partner Karl Kaiser, an Austrian-born chemist, shared a similar dream and set out to seize on an opportunity — to grow and make wine from vinifera grapes.

Ziraldo grew the grapes — riesling, chardonnay and gamay to start — at a little vineyard in Niagara and Kaiser, the winemaker, used the new grapes as the basis for these bold new wines. They received a manufacturing permit in 1974 and they were on their way. With wines to sell, and no new retail licences issued in Ontario since Prohibition, Ziraldo approached the Liquor Control Board of Ontario and convinced the government agency to grant them the first licence since Prohibition in 1929, thus ending the dominance of the six big blending wineries that controlled the only licences in Ontario.

With a means to sell their wines and a commitment to make 100% Canadian wine from vinifera grapes, Ziraldo and Kaiser started up a boutique winery in 1975 called Inniskillin, opening the door for others to follow. It started what is today the modern wine revolution in Canada.

“As a young, naive 20-something it was a challenge and several people like Robin Scott (Bank of Montreal), General George Kitching (head of the LCBO), and Bob Welch (deputy premier of Ontario at the time), believed in us. The only obstacle was skepticism which probably worked in our favour … no one saw us coming,” Ziraldo reflects today.

“As a young, naive 20-something it was a challenge and several people like Robin Scott (Bank of Montreal), General George Kitching (head of the LCBO), and Bob Welch (deputy premier of Ontario at the time), believed in us. The only obstacle was skepticism which probably worked in our favour … no one saw us coming,” Ziraldo reflects today.

•••

While granting new winery licences started an explosion in Ontario, the Okanagan Valley in British Columbia was well on its way to a revolution of its own. With help from the provincial government, over 4,000 vinifera vines were planted at 18 different sites in 1974 with gewurztraminer, riesling and pinot blanc showing the greatest promise. Up until that point, the most popular plantings in the Okangan were labrusca and French hybrids.

Harry McWatters blew onto the B.C. wine scene in 1979 when he established Sumac Ridge Estate Winery in Summerland. He lobbied the B.C. government to licence “estate” wineries with smaller wine production numbers, 15,000 cases and under, and a new era in wine began for the provincial wine industry — it created proliferation of new wineries planting vinifera grapes and making exciting wines from Canadian grapes.

Harry McWatters blew onto the B.C. wine scene in 1979 when he established Sumac Ridge Estate Winery in Summerland. He lobbied the B.C. government to licence “estate” wineries with smaller wine production numbers, 15,000 cases and under, and a new era in wine began for the provincial wine industry — it created proliferation of new wineries planting vinifera grapes and making exciting wines from Canadian grapes.

While McWatters worked quietly to establish Sumac Ridge as a premier winery in Canada, the industry was split between the “quality” wine producers and those still churning out hybrid blends. That rift was the catalyst for the most profound change in the industry that was starting to take shape. With McWatters in B.C. and Ziraldo in Ontario, a plan was being hatched to recognize wines that were made only from Canadian grapes.

The year was 1988 and three remarkable events occurred that would have a lasting impact on the Canadian wine industry — free trade with the U.S., a major grape vine pullout and replacement program with quality vinifera and the establishment of the Vintners Quality Alliance.

Free trade prompted an adjustment in the Canadian wine industry. To conform to the new reality and with a desire to produce premium wines in this country, Ontario and B.C. growers agreed to a major federal-provincial program to replace native grapes with vinifera. With the new varietals and a commitment from quality producers such as Inniskillin in Ontario and Sumac Ridge in B.C., VQA was established.

In 1988, Ontario was first to establish the new set of rules, which was a quality assurance program that meant consumers were buying wine that was made with 100% Canadian grapes. B.C., with McWatters as a driving force, followed suit two years later in 1990.

In 1988, Ontario was first to establish the new set of rules, which was a quality assurance program that meant consumers were buying wine that was made with 100% Canadian grapes. B.C., with McWatters as a driving force, followed suit two years later in 1990.

“Without VQA we wouldn’t have an industry today,” McWatters said. “We wouldn’t exist today.” For McWatters the establishment of a quality assurance board was the turning point in Canadian wine history. “It’s gone beyond what I believed could happen. I had no idea of the potential.”

•••

Harry McWatters and Donald Ziraldo have had a front-row seat for the wild ride that has been the Canadian wine industry and have been a part of its dramatic growth since the 1970s. But they haven’t been alone. Paul Bosc (Chateau des Charmes), Len Pennachetti (Cave Spring Cellars), John Marynissen (Marynissen Estates Winery), Ewald Reif (Reif Estate Winery), George Heiss (Gray Monk), Robert Shaunessy (Tinhorn Creek), and Anthony von Mandl (Mission Hill) all helped shape the industry by believing in a product that was proudly and totally Canadian.

In the mid-1970s there were scant few wineries operating in either the Okanagan Valley or Ontario. And even fewer committed to producing Canadian wine. Today the number of wineries — from the wonderful fruit wineries in almost every province to those in the emerging regions of Nova Scotia, Prince Edward County in Ontario, the Gulf Islands and Vancouver Island in B.C., Lake Erie North Shore, Pelee Island and the major regions of the Okanagan Valley and Niagara Peninsula — is fast approaching 500.

In the mid-1970s there were scant few wineries operating in either the Okanagan Valley or Ontario. And even fewer committed to producing Canadian wine. Today the number of wineries — from the wonderful fruit wineries in almost every province to those in the emerging regions of Nova Scotia, Prince Edward County in Ontario, the Gulf Islands and Vancouver Island in B.C., Lake Erie North Shore, Pelee Island and the major regions of the Okanagan Valley and Niagara Peninsula — is fast approaching 500.

And the best is yet to come as new dreamers emerge from their garages, back sheds and basements with even better wines, raising the bar and testing the boundaries of an industry that shows no limits. Now, that’s something we can all drink to.

“… an industry that shows no limits.” … dare to dream and export to Europe. Or at the very least, don’t disable web shops from delivery there. Is it provincialism squared, or export restrictions from a century back ..? How am I supposed to enjoy a good NotL wine over here (Netherlands) ..? Not that there are many that would fit a European style and taste (much too much is still American-oriented sugar with grape juice) but there’s some exceptions — which can’t be had over here. Why oh why ..?

[No bashing intended, just curious…]

Great article. As a recent seasonal resident and long time visitor to Nova Scotia I’m learning that with a little careful experimentation there are some good wines coming out of Canada. Given the difficulty of getting decent affordable wine from most anywhere in the world at a NSLC store, it’s been a pleasant surprise to discover Canadian wine.

Thanks, Brian, for your comments. Canadian wines, in general, are a little more expensive than wines from other regions, but I don’t think Canada is trying to compete at the entry level. Making small-batch wines with personality from low-yielding vineyards is really our forte. Glad you’ve found some you like. Nova Scotia is doing some very fine wines.