We’re digging into a hearty harvest lunch of lasagna, garden salad and gooey butter tarts brought in by a caterer to feed the hungry crew at Tawse Vineyards.

A few bottles of Tawse wines are scattered around the table that comfortably seats 16 workers, 12 hired to work the harvest and four full-time winery staff. And there is a mystery bottle on the table wrapped in tinfoil. Small amounts are poured into each glass. We are asked to guess what it is and where it’s from based on taste and smell.

Winemaker Paul Pender — who leads this strapping multi-national crew of young men and women from places as far flung as Argentina and Australia and closer to home, Niagara College and Toronto — looks at the bottle, swirls the wine, tastes it, looks back at the bottle and declares: “Well, it’s not from France,” he says noting the screwcap top that’s peaking out of the foil.

Another moment or two of swishing and swirling and he declares with quiet confidence, “It’s from Australia. Syrah, NOT Shiraz, cool climate,” he says.

Everyone else takes their best guess but it is all for naught. Pender nails it, even the subtle stylistic difference between Syrah and Shiraz, as wineries in the cooler climes of the Adelaide Hills are prone to call their wines. The bottle is revealed and, sure enough, it’s a Ngeringa Adelaide Hills Syrah.

It can’t be much fun playing that game with Pender. But he is a gracious winner, something he’s had a lot of practice at.

It can’t be much fun playing that game with Pender. But he is a gracious winner, something he’s had a lot of practice at.

Tawse, as you’ve undoubtedly heard by now, just picked up the Canadian Winery of the Year for 2011, the second year in a row the editors at Wine Access Magazine have awarded the Vineland winery that honour.

It’s a fitting accolade.

Tawse churns out an excellent portfolio of terroir-driven wines made from organic-biodynamic vineyards vintage after vintage. It’s one of Niagara’s prettiest and most modern wineries, utilizing gravity through the entire winemaking process.

Winery owner, Moray Tawse, has made all the right decisions in creating the winery and putting together a philosophy that’s being carried out by Pender and his team precisely as Tawse envisioned it (well, OK, with a few twists and turns along the way).

First and foremost is sustainable farming at the estate and surrounding vineyards and the strict practices that being bio-organic certified means through the entire winemaking process. And then delivering the concept to a dedicated following who not only buy into the wines but appreciate the quality that goes into the predominantly Burgundy-inspired Chardonnays and Pinot Noirs along with the other varietals that do well in Niagara including single-vineyard Rieslings, Cabernet Franc and icewines.

Pender had given me the news on the Wine Access award while visiting the winery during a prolonged rainy spell last week. I had come to talk about the growing, some say controversial, “natural” wine movement that is gaining traction in the world of wine.

I have become interested in these wines lately and wanted to know if any Niagara wineries were attempting to make natural wines locally. I tweeted that very question and Pender responded almost immediately that he was making what he considers natural wines. That piqued my curiosity and we agreed to meet and talk about it.

The mere mention of “natural” wines strikes general discord among wine lovers. It’s been called many different things — naked, live, naturel, among them — and it has its critics and supporters on both sides of the fence.

Under the strictest of definitions, perhaps the most severe description comes from Alice Feiring, author of Naked Wine, on Cory Cartwright’s excellent Saignee blog. Here she describes in a letter to Cartwright what “Vin Nature” wines are not:

“Any wine that deploys aromatic yeasts, enzymes, bacteria, new oak, toasted oak, oak additives, tannins, gum arabic, reverse osmosis for concentration or alcohol removal, spinning cone, excessive sugar, mega-purple thermo-vinification, cold-soaking, anti-foaming agents, ultra-sulfuring and god knows what else, in any combination, is far from natural. To argue the point is being combative, or desperate.”

Feiring’s simple definition of what natural wines are, which leaves room for interpretation and debate, is this:

“Nothing added, nothing taken away.”

I had heard that one of the finest wine shops in Boston, The Wine Bottega, specialized in natural wines.

I visited the shop this summer and met Matt Mallo who showed me around the well-stocked wine store. What a gorgeous shop. An adventure into small production wines from up and coming (and seldom seen) regions and, yes, a lot of bio-organic wines and a nice selection of so-called Vin Nature wines. I bought a few, tried them and enjoyed them for what they were: Imperfect wines that had that gritty-dirty taste you’d expect from wines that had not been manipulated in any way in the winery.

I like Mallo’s less severe definition of natural wine:

“Possibly the most controversial banner of our day, the term “natural wine” really means nothing at all. There is no governing body or book of guidelines to making vin natural. In general, when we at the shop speak of natural wine we are talking about producers that work the vineyards without chemicals, they sometimes use biodynamic principles (sometimes not). They cultivate healthy grapes, which they allow to ferment without the addition of commercial/industrial yeasts, colour stabilizers, acid adjustments, etc. Basically, natural wines are those that haven’t been messed around with. Where organic wines stop at the cellar door, natural wine merely begins. It’s about the simplest and most honest expression of the terroir through the medium that we call wine.”

Which is where Pender comes in. In that description, Pender’s bio-organic philosophy and non-interventionist routines more closely follow Mallo’s vin natural protocols then Feiring’s definition.

The sticking point for most sustainable wineries, of course, is the use of sulphur, an essential component in the making of wine.

Sulphur dioxide (SO2) is used to inhibit or kill unwanted yeasts and bacteria, and to protect wine from oxidation. If you are commercial winery and want to be successful, this is a crucial step not to be missed. And not using even small amounts of sulphur is a risk most winemakers do not want to take (and fewer winery owners).

The term natural means “nothing” to Pender and he views it as such a generic term now, on a whole range of products, that it has no meaning.

At Tawse “we try to be as natural as possible,” he says, but he’s not about to make “natural wines” under the strictest definition out there.

Pender farms organically and biodynamically, uses natural yeasts in 70% of his estate wines, gravity-flow winemaking and follows rules through the winemaking process governed by bio-organic principals.

“Natural wine in its purest form is going out to the vineyard and eating a grape,” muses Pender.

“You can never be dogmatic. There is no room for dogmatism in winemaking because by noon you’re making compromises. Stuff happens and you need to react.”

Pender uses sulphur as an anti-bacterial agent in winemaking. “It hampers the bad yeast and favours the good yeast,” he says.

“We need good, clean ferments to make wines with a sense of place. Terroir needs to be clean. We don’t want any faults in the wine.”

Natural wines? “I don’t think it’s the way to go.”

By way of example, Pender offers a sample of the Quarry Road Chardonnay 2010 that he’s having trouble getting to undergo malolactic fermentation. It’s un-sulphured and essentially undrinkable with bitter, phenolic, bad whiskey flavours. Essentially dirty and unpleasant compared to the same Chardonnay that’s seen sulphur. That sample is fresh with minerals, citrus and rounded fruit flavours. It’s the same wine, sulphur vs. non-sulphur, with striking differences.

For Pender, nature happens in the vineyard. “This where you can really delve into a wine. Stand back, watch it happen in the vineyard. Don’t try to get in the way or manipulate the flavours. Nature has a better way,” he says.

•••

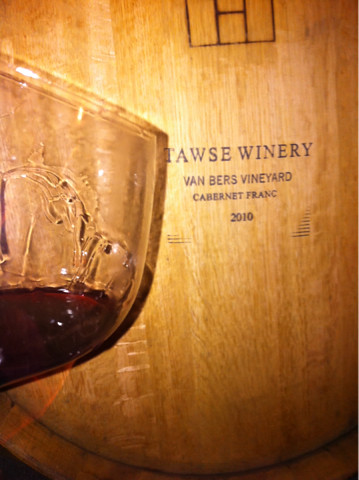

I finish my visit with Pender with a barrel tasting of the much-anticipated 2010 reds now simmering away in oak barrels.

He first pours a sample of the 2010 Van Bers Vineyard Cabernet Franc. It’s truly unbelievable with rich, highly extracted black fruits and texture, already showing signs of the best Cab Franc made at the estate to date.

Ditto for both the new Redstone Vineyard Syrah and the Redstone Merlot from the Lincoln Lakeshore appellation. Both thick, rich and layered reds that show great promise in barrel.

These are wines of substance, a sense of place and made as naturally as possible without wrecking the wine.

But that’s just my opinion.

•••

Here’s a review of one of the natural wines I purchased at the Wine Bottega in Boston:

Jean-Yves Peron VdP d’Allobrogie Champ Levat 2009, Haut-Savoie, France ($25, 90 points) — A fascinating red wine made with 100% Mondeuse, a rustic version of Syrah, and follows the natural winemaking principals of “nothing added, nothing taken away.” In other words, wild fermentation, no sulphur added, organically farmed vineyards. It shows a crazy-wild nose of fruitcake, spice, cinnamon, cloves, violets, sun-baked raspberry and black currants. In the mouth it’s bone dry, slightly oxidized, tight and highly acidic with flavours of crushed flowers, loam, mineral, aggressive tannins, peppery spice, raspberry, cranberry and boysenberry. Not for everyone, but a thrill if you’re looking for something on the wild side.

Enjoy!

Comment here