It was a decade ago that the shocking news was delivered: On June 1, 2006, Canada’s largest and most successful wine company Vincor was officially sold to the gigantic American company Constellation Brands for $36.50 a share plus a 15% dividend.

Vincor was a company built from the ground up by an ambitious core of dreamers; Donald Triggs and Allan Jackson (Jackson-Triggs Winery), Karl Kaiser and Donald Ziraldo (Inniskillin), and, in the west, Harry McWatters (Hawthorne Mountain, renamed See Ya Later Ranch and Sumac Ridge) were the most visible.

Their success was their un-doing, as they collected wineries, not only in Canada, but the entire world, and grew to become an attractive takeover target for Constellation.

As news broke Monday (full story here) about the sale of Constellation’s Canadian assets (and Canadian distribution rights to such juggernauts as Robert Mondavi and Kim Crawford wines) I couldn’t help but think about Vincor’s former executives and what was going through their minds as they learned the company they built was coming back to Canada.

I had written many times in the past of how the deal went down (see below) and the sense of sadness the former Vincor crew all felt at the loss of their company.

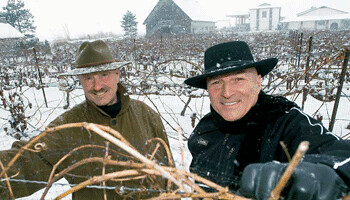

With the exception of only Kaiser, above right with Donald Ziraldo, who retired just recently and stayed on the longest with Constellation, all the key players continued to find success with their own wineries and second careers:

Donald Triggs: Culmina Winery in the Okanagan Valley;

Donald Ziraldo: Director of Senhora Do Convento Winery in the Douro Valley, Portugal. Vintner/owner of Ziraldo Estate Winery;

Allen Jackson: Union Wines in Ontario;

And Harry McWatters, Time Estate Winery, Evolve Cellars and McWatters Collection all in the Okanagan Valley.

In a wide-ranging interview about the Constellation deal today, McWatters was positively excited to see his former Vincor back into the hands of Canadians. As was Inniskillin co-founder Karl Kaiser.

“It’s a really good thing for the industry,” he said. The values of Vincor are more in line with what Canadians want to see. And the profits will stay in Canada. That’s big,” he added.

McWatters believes the buyers of Constellation’s Canadian assets, the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Fund, is smart enough to step aside and let a knowledgeable team handle the day to day business of running a mega-wine business.

“They need to empower their people at all levels. It’s been taken away over the years (by the U.S. arm of Constellation). They have a big talent pool to draw from.”

McWatters believes Jay Wright, currently Constellation’s president, wine & spirits, Canada, and hired by that company in 2006 to run the Vincor properties in Canada, is positioned to return to Constellation Canada to its core values.

“Jay has lived on both sides of it (Vincor and Constellation). He’s capable of putting together a good team,” McWatters said.

“I can’t see anything negative in this deal at all, but the devil’s in the details.”

Asked if McWatters would entertain coming back to the company he helped build, he was diplomatic.

“I enjoyed my time at Vincor, but I didn’t last long at Constellation. My plate is pretty full these days and … I don’t think they’ll be asking us.”

Kaiser, the master of Inniskillin’s wine program for so many years, and the man who made the most famous wine in Canada’s history — Inniskillin’s celebrated 1989 Vidal icewine, which won the Grand Prix d’Honneur at Bordeaux’s 1991 Vinexpo wine fair — has done what none of the other Vincor executives has done. He fully retired in 2006 from the business he loved so much.

After a few years as head of quality assurance for Vincor Canada under the new company and icewine maker at Inniskillin until 2006 and some part-time consulting, Kaiser took some time to travel and do some teaching at Brock University.

The last commercial wine he made was the most expensive icewine ever at the time — a commemorative 2004 oak-aged Cabernet Franc Icewine that went on sale for $450 a bottle.

He’s happy now making wines for himself, his family and his pals from purchased grapes and equipment he’s acquired throughout his career. He makes about 45 cases of Sauvignon Blanc and a Bordeaux-style blend and divides it up with three friends every year.

He’s happy now making wines for himself, his family and his pals from purchased grapes and equipment he’s acquired throughout his career. He makes about 45 cases of Sauvignon Blanc and a Bordeaux-style blend and divides it up with three friends every year.

“I think it is good that the old ‘Vincor’ company is in Canadian hands again,” Kaiser said Tuesday. “So, first of all, the ‘Constellation Brands’ name will be gone and corporate decisions will not be made in Rochester, N.Y., but in Mississauga.”

“Some top management will be replaced. How capable the Teachers are to find first-class replacement has to be seen,” he said.

“Since Peller was for a while the largest Canadian winery, this step by the Teachers might make the old Vincor the largest again in Canada … but I don’t think you (will) see a change right away in their product line.”

Background on McWatters’ role with Vincor

Harry McWatters is to the B.C. wine industry what Donald Ziraldo is to the Ontario wine industry. He blazed a trail that others follow to this day.

When Ziraldo, above, fought for VQA designation in Ontario, McWatters followed in B.C. In 1988, with Ziraldo being the driving force, Ontario was first to establish VQA, a new set of rules that meant consumers were buying wine that was made with 100% Canadian grapes. B.C., with McWatters leading the charge, followed suit two years later in 1990.

Together the dynamic duo took the quality of wines in Canada to new heights with a level of quality most wineries in Ontario and B.C. strived to achieve.

McWatters founded Sumac Ridge and bought Hawthorne Mountain (later named See Ya Later Ranch) and built them into two of the most recognizable Okanagan wineries before joining the mega-bus that was Vincor, and giving the new company needed clout on the West Coast.

McWatters has always been the consummate storyteller and an ardent support of VQA wines in Canada. His knowledge and expertise is unsurpassed.

When he sold his wineries to Vincor, he stayed with the new company in the key role of promoting and standing watch over the products he built. He agreed to be part of Vincor for “as long as Don Triggs (shown above) was there.”

The day the hostile bid from Constellation arrived, McWatters was in Tuscany but he knew the end was nigh. All that was left was negotiating the best deal for shareholders.

McWatters stayed on longer than most, consulting for three years and all the while setting up his own consulting business.

Today, McWatters’ Vintage Consulting Group is a wide-ranging business that helps wineries get started with viticultural and winemaking expertise, vineyard assessment, marketing and even cellar assessment. His services are sought after across the county.

And, as if that wasn’t enough, McWatters launched his own legacy brand of Okanagan icon wines, the McWatters Collection and also started Time Estate and Evolve Cellars.

His McWatters Collection, a small production of Chardonnay and Meritage is made from his Sundial Vineyard, which is really the famed Black Sage Vineyard (the name is now a trademark belonging to Constellation Brands when it bought Sumac Ridge), one of the most coveted vineyards in the South Okanagan.

“I don’t have a lot of hobbies,” McWatters says. “I love what I do and I’m going to keep my foot on the pedal. I’m having fun with it.”

The Vincor deal to Constellation

The seeds for Vincor were sown in 1989 when Donald Triggs and Allan Jackson bought Ridout Wines (where Triggs had been president until 1982), the wine division of the Canadian brewing company John Labatt, Inc.

Labatt wanted to get out of the wine Canadian business that, at the time, was predicting a dramatic loss of market share due to recent free trade laws that foreshadowed an influx of lower priced imported wines flooding the market.

Jackson had been VP of operations at Chateau Gai, then under the Labatt umbrella, and he, along with Triggs orchestrated the management buyout.

The growing team then set their sights on quickly building the Canadian company with acquisitions and mergers to build cash flow and pay down the debt (which they did within two years) incurred by buying Ridout.

Niagara author Linda Bramble, in her book Niagara’s Wine Visionaries, said in her chapter on Donald Triggs:

“Triggs always saw the future in premium wines. Being a pragmatist, he figured there were two ways of developing that vision: by developing their own brands and vineyards or by acquiring or merging with the best premium wineries that they could afford to buy.”

Triggs and Jackson chose to pursue both segments of the market under their new company they named Cartier Wines. First they attacked the higher-end market when they merged with Niagara’s Inniskillin Wines, founded and owned at the time by Donald Ziraldo and Karl Kaiser. It was a mutually beneficial arrangement — Inniskillin gained a broader retail presence and Cartier established itself in the premium and ultra-premium wine category.

The company was renamed Cartier-Inniskillin Vintners and the big job of producing enough wine to feed the bottom line began in earnest.

The next major hurdle for Cartier-Inniskillin was the reverse buyout of Brights, which owned considerable wineries in B.C., Ontario, Quebec and Nova Scotia. It would be a difficult merger melding two very different cultures, but when the smoke cleared, wrote Bramble, the company had changed its name to Vincor Canada and now had “significant efficiencies of production and scale and a massive and dynamic sales force across the country.”

In 1993, Vincor established the Jackson-Triggs brand. The winery initially produced only two wines, a Chardonnay and a Cabernet Sauvignon. The wines were made partly with Ontario grapes, supplemented by grapes from Chile and California. The wines were an immediate hit, and over the next five years the brand became one of the top 10 bestselling in Canada. The winery wasn’t built in Niagara-on-the-Lake until 2001 and would become the largest VQA brand in Canada, selling 250,000 cases annually.

When Vincor went public in 1996, raising $40 million at $8 a share, the acquisitions came swiftly: London Winery, R.J. Grape, Spagnols, Hawthorne Mountain (bought by Harry McWatters and renamed See Ya Later Ranch) and Sumac Ridge (founded and owned by McWatters).

It also developed Le Clos Jordanne (in partnership with Boisset, and the Okanagan’s Osoyoos Larose (in partnership with Groupe Taillan). The Le Clos brand is now dead, Osoyoos Larose was sold.

It then moved on to the international wine community buying R.H. Phillip, Hogue Cellars, Goundry, Kim Crawford and, perhaps its undoing, the South African brand Kumala.

As Bramble said, “hardly a year went by that they didn’t mark with an acquisition.”

It was selling one out of every 4.5 bottles of wine sold in Canada by 1999. It would rise to become the fourth-largest wine company in the North America and the seventh largest in the world at its peak.

Then the big blip; shares plunged 13% in 2005 following disappointing numbers from Kumala. Waiting in the wings like a tiger stalking its prey, was the largest wine company in the world, Constellation Brands, which wasted no time in launching a hostile bid to acquire Vincor for $31 a share, a deal worth $1.4 billion.

It was an unwanted bid to buy Vincor, but Triggs outsmarted Constellation CEO Richard Sands, and convinced shareholders the company was worth much more than that. Vincor knew it was doomed; all that was left was getting the best possible price from the hostile takeover.

On June 1, 2006 Vincor was officially sold to Constellation brands for $36.50 a share plus a 15% dividend. The dream was over, but the profit form the original $8 shares enabled a lot of new dreams to be born.

Comment here