By Rick VanSickle

Turmoil, uncertainty and fear for the future is staring the Canadian wine industry square in the eye these days — and it goes far beyond pandemic related.

Already reeling from COVID-related losses due to five months of operating in survival mode just to keep the lights on, few Canadian wineries will escape some sort of financial loss in 2020. The impact of no on-site retail sales for several months combined with lack of tours, tastings, weddings, events and restaurants not purchasing VQA wines is a blow that will affect the smaller to medium-sized wineries the hardest. Wineries that have a restaurant or food as part of their facilities, though now back open but with fewer tables, also took a hit with doors shuttered to all but take out for the first few months of the pandemic.

Wineries have said that sales are up for local VQA wines at the LCBO and many have seen an uptick in online sales driven partially by wide spread free delivery. But it is nowhere near enough to cover the losses in 2020.

Then comes the latest blow to the industry with Canada and Australia announcing a partial agreement regarding Australia’s World Trade Organization (WTO) challenge to Canada regarding the rules applied to wine sales in this country. In 2018, Australia filed the complaint, saying a range of distribution, licensing and sales measures such as product markups, market access and listing policies — as well as duties and taxes on wine applied at the federal and provincial levels in Canada — may discriminate against imported wine.

As is, the tax exemption for Canadian wine producers costs the federal government about $40-million a year. Since the program’s inception, an industry of 300 Canadian wineries has grown to include about 700, many of which are small labels producing small batches of premium, world-recognized vintages.

The end of the exemption will mean a 50-cent per bottle hit to wineries, according to Dan Paszkowski, president of the Canadian Vintners Association. Already operating on thin profit margins, producers will soon face a difficult choice — absorb the lost exemption or pass the costs along to the consumer, and neither is a good option. The repeal takes effect June 30, 2022.

“It will be difficult for our sector to pass on those costs,” Paszkowski told the Financial Post. “For the smallest wineries in this country the loss of the excise exemption will be the nail in the coffin, it is that serious.”

He predicts “hundreds of wineries” could be lost if the federal government, in concert with the industry, can’t arrive at some new form of subsidy to replace the exemption being axed.

“The loss of the exemption could not have come at a worse time for the industry. With COVID, with flat wine sales, with restaurants and bars not being at full capacity, it is going to cause significant, significant pain,” Paszkowski said.

The WTO challenge from Australia comes at a time when that once powerful wine nation is now bleeding market share around the world.

“Removing these trade barriers will mean our wine exporters can now compete on a level playing field with Canadian wine producers,” Australian Federal Trade Minister Simon Birmingham said in a statement. “With Australian wine exporters enjoying zero tariffs into Canada, this is a market with real potential for growth and this agreement will provide further opportunities for our wine exporters to sell more Australian wine in Canada.”

Canada is already Australia’s fourth-largest export market for wine, and it is the fourth-largest supplier of wine to the Canadian market, in terms of value, and second largest in terms of volume sold. Add all the numbers together and Canada represents a $185-million annual business for Australian winemakers.

Sadly, that revenue is not reciprocated. According to numbers provided to Wines In Niagara by Global Affairs Canada, a total of 450 litres of Canadian icewine (about 5.5 bathtubs full, if you need a very depressing visual) are were exported to Australia in 2020 up to May. In all of 2019, 1,615 litres of wine, 18 litres of sparkling wine (that’s like a backyard BBQ), and 450 litres of icewine, were exported to Australia. That’s a total of 2,083 litres, or about 22 bathtubs full. The Aussies thank us for our generosity.

In light of that, some might call Australia’s WTO challenge hypocritical. Australia’s winemakers benefit from a tax-equalization plan at home, a government gift that remains intact as they fight that very thing abroad. Think about that for a moment.

In many circles, talk of a consumer ban on Aussie wines is being discussed, however, bans as such rarely work. And, really, Australia is just being smart in finding a weak spot in Canadian trade law. It’s not their fault, it ours. On its own merit, or simply because tastes of Canadian wine drinkers have changed, sales of Australian wines have dropped from a high of $233 million annually to $175 million today. And it’s not because, as the Australians maintain, Canadian retailers hide their wines under file cabinets in the basement of the LCBO.

The Wine Growers of Canada (WGC) said in a statement last week that the Canadian wine industry needs a commitment to an “excise exemption replacement program” following news of the WTO decision.

In the statement, WGC cited: the financial impacts of losing the excise exemption; greater access to imports under recently negotiated CETA, CPTPP and NAFTA trade agreements; and now the COVID-19 pandemic.

“With already slim margins, the excise tax burden threatens the profitability and ultimate survival of wineries across Canada,” the statement said.

WGC said the exemption supported investment in over 400 new wineries and 300 winery modernizations, stimulating sales growth of 40 million litres of 100% Canadian wine.

As well, the group said Finance Minister Bill Morneau confirmed with them that Ottawa is prepared to support the wine industry in managing the impacts of this trade challenge, and “(is) actively investigating options that align with Canada’s international trade obligations, with a view to ensuring the long-term success of the industry.”

Meanwhile, Ontario’s craft wineries have started circulating a petition in support of the province’s family-farm wineries and are targeting yet another tax imposed on them.

Ontario’s craft wineries are, for the most part, locally owned, family-farm businesses that create jobs, attract tourists, and support Ontario agriculture, the petition reads. Even before the COVID pandemic hit and tourism all but dried up, Ontario’s family-farm wineries were hurting – big time. All because of unfair taxes.

For example, the petition reads, did you know that Ontario wineries are forced to pay a 6.1% tax per bottle of VQA wine sold at their own wineries to the Ministry of Finance – even when the government and other regulatory bodies play no role at all in selling?

“This unfair tax punishes local farm families for selling their own products on their own properties,” the petition reads.

Ontario wineries maintain that eliminating what they call an unfair tax would help small wineries hire staff, invest in resources to provide greater experiences to their consumers, obtain new equipment for winemaking and retail operations, and more.

“As Ontario’s economy struggles to recover from the COVID crisis, Ontario’s craft wineries need tax fairness and relief now more than ever. Their ability to survive depends on it,” the petition reads.

“Unfair taxes and outdated regulations were already hurting the wine industry, but coupled with the near shutdown of the economy, this is the biggest existential threat small wineries have ever faced.”

You can sign the petition here.

Bill Redelmeier had a good explanation (in a letter to his mailing list) of the 6.1% excise tax imposed on Ontario wineries and why it should be revoked.

“While excise taxes should be applied fairly and legally, when we sell wine at our retail, online or to restaurants, we have to pay an LCBO “handling fee” of 6.1%. Only on Canadian or VQA wines. The LCBO doesn’t touch (or handle) the wine. When you buy imports through Wineonline or Vivino they don’t pay it. Now that agents are allowed to sell mixed cases of imported wine directly to consumers, they don’t pay it,” he said.

“Notice that the offers that they send out never offer Canadian wine? That is because they would have to pay 6.1% to the LCBO for a handling fee, so they don’t offer them. I have asked members of the Ontario wine industry with longer memories than me, and no one can remember where the 6.1% fee came from. We think that this is odd that only Canadian wines are charged this, and now is a good time to get rid of it. If you agree, I would love you to sign this petition, and even better, to pass it on to friends, and your MPP.

“Not to whine too much about it, but when a wine producer in Ohio puts a bottle out in his store for $19.95, he gets to keep $19.91. That is right. All but 4 cents. When we sell a bottle at our winery retail store, for the same price, we get to keep $19.95, less $0.20 (bottle deposit) less $2.27 (HST) less $0.98 (LCBO admin/handling) less $0.09 ( environmental levy) less $0.22 (bottle tax). That leaves us $16.18.”

Meanwhile, the disturbing news doesn’t end with Australia’s battle for fairness in Canada or over-taxed Canadian wineries, the largest issue right now vintners will have to deal with are the grapes growing on the vines.

Lax sales due to COVID means wine some wine will inevitably go unsold and even unbottled and pushed ahead to 2020 for blending (which is legal, and in fact, can be labeled as a non-vintage wine under revamped rules). Heading into the sixth month of the pandemic, with the vast majority restaurants still not open to any degree and limited space at wineries for retail and tasting, it’s hard to imagine it being a banner year for selling wine. There’s an irony there — 2020 is shaping up to be a gorgeous vintage.

In fact, if you look at the Grape Growers of Ontario website classified section, seen here, there is well over 1,000 tonnes of grapes under vine for 2020 not yet sold and all kinds of rumours of grape contracts being cancelled. That’s an indication of what wineries think they will need to bolster their estate fruit. And it’s not much. They just aren’t buying anything extra, if the numbers continue to climb like that.

The Grape Growers of Ontario, under unique circumstances, came to a consensus this week with Ontario’s wine processors on the 2020 wine grape prices. After a full day of negotiations last week, in a reflection of the new reality, grape growers and the association agreed to an overall 1% increase for grapes. Last year the growers received a 2.8% increase.

“The moderate price increase reflects the current global situation and pandemic, and provides the opportunity for the industry to focus on our core business of growing and selling more 100% grown in Ontario wines,” said Matthias Oppenlaender, chair of the GGO.

“We have a collective interest in the continued growth of the Ontario grape and wine industry, which is a significant economic driver of the provincial economy. Wine made of 100% Ontario grown grapes generates $98 of economic impact per bottle,” said Debbie Zimmerman, CEO of GGO.

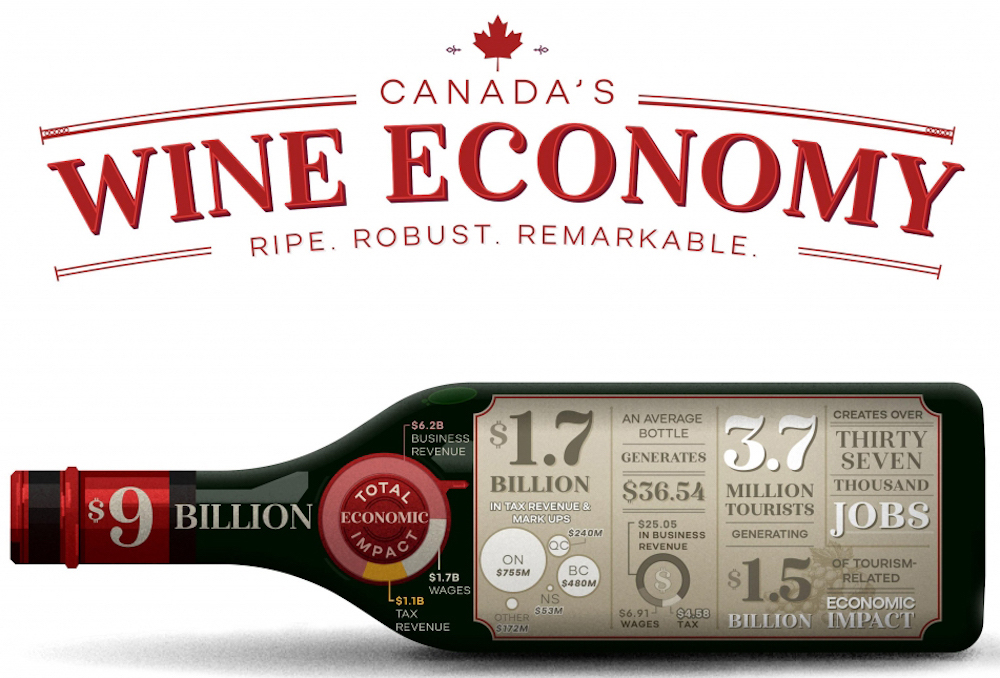

Ontario’s grape and wine industry contributes over $4.4 billion in economic impact through jobs, tourism and taxes, particularly in the province’s designated viticulture areas.

And right now the industry could use a little help. Buy local, sign the petition and speak up. Never has there been a better time to buy Canadian wine.

Can you please explain to me why Oliver, B.C. has the the distinction of calling itself the wine capital of Canada? I live in Toronto and love the Niagara region in general, Niagara on the Lake specifically. However I’ve spent considerable time in Oliver as my husband’s family is there. I just don’t get it. It’s a one horse town without one decent hotel. There are only a couple shabby motels. I’ve visited all the wineries there but there’s only a fraction of the choices that there are in Niagara. I love wine but I’m not an expert. I realize both areas must have the right ecosystem for wine growing, but I feel this distinction is dubious if not downright deceiving and it should be moved to Niagara. Anyone who’s spent time in Oliver would realize it’s laughable to refer to it as the capital of anything.

Thanks for the question, Jean. It comes down to this: You can declare anything you want, but it doesn’t make it so. A fellow by the name of Kenn Oldfield (formerly the owner of Tinhhorn Creek Winery, located in the Oliver area) is credited with the idea. Here’s is what he said about it. “Before 2001, we had put together an economic development company for Oliver. There was a board of us, and we hired an economic development officer to develop a plan. We already had the Festival of the Grape – since 1997 – and somebody said, ‘Oliver was once the cantaloup capital of Canada, but now that we’re growing grapes let’s call it the grape capital of Canada.’ Across the table, another board member said, ‘good idea, but there’s no sex in grapes. The sexiness and the vision, for people is in Wine Capital of Canada. We’re making wine out of these grapes, so can we make a case for that? That’s where I came in. I said ok, lead me to it.”