By Rick VanSickle

The threat of acquiring the so-called “cellar palate” is very real for many of the hard-working souls in wine regions around the world, and that includes Niagara.

“Suffering from ‘cellar palate’ means that you’ve become so immersed in a local style that you become blind to the faults or shortcomings in the wines,” wrote Matt Walls in Decanter. “It’s a condition more commonly associated with winemakers, but it can affect anyone tasting lots of wines from a specific region, such as wine critics or even holidaymakers (people on vacation).”

Walls explained to his readers that over time, your palate adapts to local norms. “If you’re aware of the problem, and take steps to mitigate it, cellar palate should be an easily avoidable condition.”

In Niagara, with so many styles and varieties grown in the region, unlike, say Burgundy, Bordeaux, or New Zealand, it’s particularly important to taste, taste, taste and taste some more far beyond your own wines and those of your neighbours. And that’s what generally occurs locally.

At harvest tables during lunch, industry gatherings for winemakers, and impromptu tastings among winemaking friends, a wide array of bottles are usually strewn about the table for comparison. Some are from neighbouring wineries and, more often than not, from the wide world of wine. It gives winemakers more perspective on what the rest of the world is making and offers a view into the styles and trends taking place elsewhere. It’s a crucial part of the job.

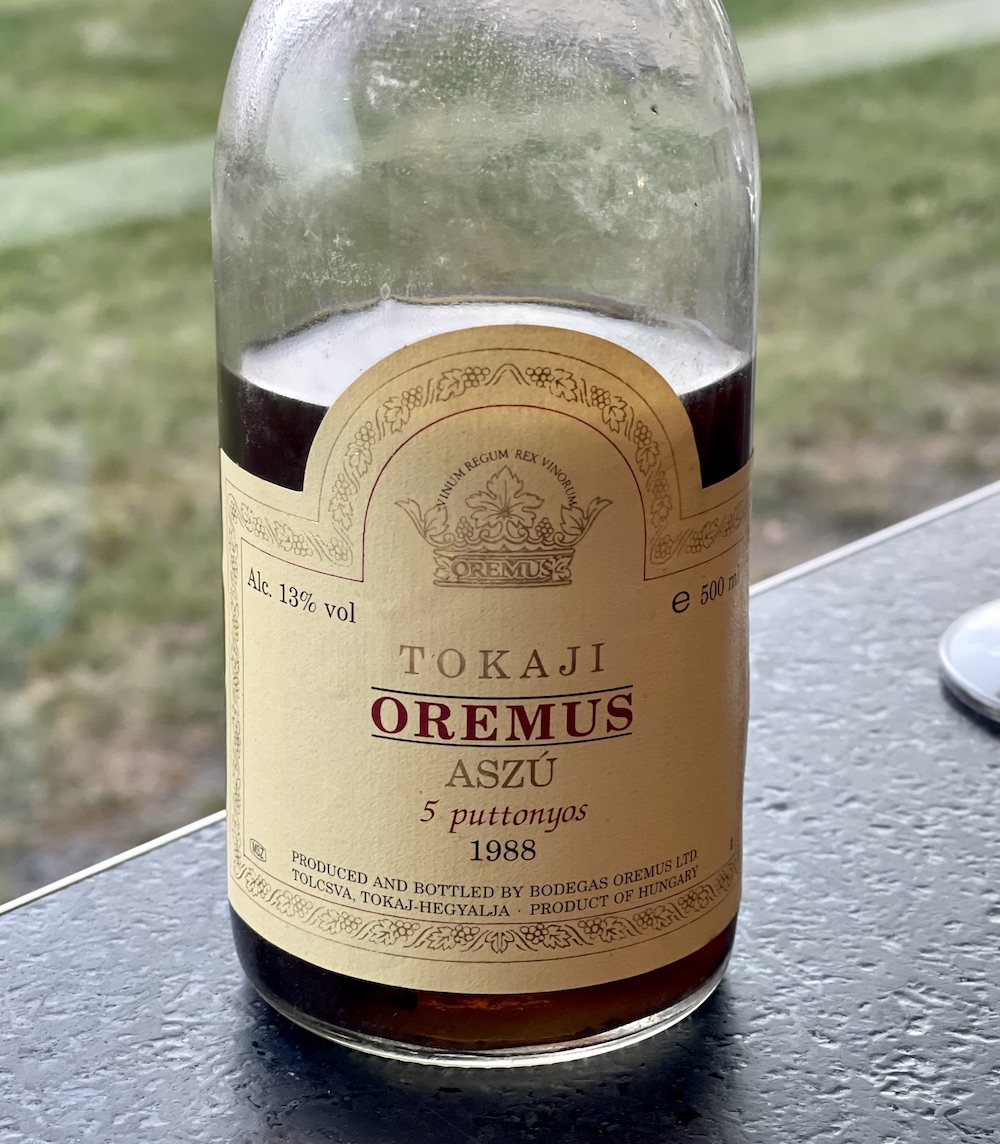

Living in Niagara and covering the wine industry has given me the opportunity to take part in many of the tastings that are conducted from Grimsby to the St. David’s Bench. Some are structured, some are more casual (like a dinner where friends bring an interesting bottle, see above photo), but all of them are geared toward expanding the palate beyond what’s coming from your own backyard. It’s something I value as a wine writer who now primarily covers only Ontario VQA wines and no longer accepts “familiarity” trips to far flung wine regions where you are fed a steady diet of some of the finest wines in the world. Yes, I make a point of tasting as many international wines as I can, and always keep a portion of the cellar stocked with my favourites, but I don’t have as much exposure to worldly wines that I used to. My palate is calibrated to Ontario wines and needs constant tweaking from time to time for a more worldly and critical view.

The most recent tasting I was invited to was at Southbrook Organic Vineyards, a leader in sustainable farming in Niagara owned by Bill Redelmeier. He holds tastings at the winery almost weekly for winemakers, friends and guests that always follow some sort of theme. He reaches deep into his own cellar for most of the wines, while a few others are brought by guests.

The tasting I attended featured sweet wines from around the world, a well-represented array of wines that painted a tidy picture of the myriad styles of these high-sugar wines and how they perform over time. This was only one part of three that featured sweet wines, because there are so many crafted world-wide. There was only one sweet wine from Ontario in the lineup, and it wasn’t even a Southbrook wine, of which Redelmeier has plenty of in his wine vaults at his winery and his home. I did see one or two lined up for the third round of sweeties coming up in the next session.

What we did taste was a thrilling rollercoaster ride of sweet wines from the 1970s all the way up to some more current vintages. It covered a wide range of styles from Niagara, Germany, France (Alsace and Sauternes), Hungary, Portugal (Port and Madeira), and Italy. These sweet wines from around the world have one thing in common in that they age beautifully. They come in an array of styles and flavours, yet age brings them closer together as they harmonize and mellow. The results were remarkable. Here is what I liked; in the order they were poured:

Chateau Guiraud Sauternes 1976 — In a lot of ways, this 47-year-old Sauvignon Blanc/Semillon blend set the tone for this spectacular tasting of sweeties. With the older vintages, it’s not about ripe fruit and finesse, it’s all about the texture and tertiary flavours. These is lush and deep on the nose with dried apricots, toffee, marmalade and burnt brown sugar. Such wonderful richness and a silky texture on the palate with macerated exotic fruits, honey, toasted almonds and still a little finesse hanging in there. Past its prime, for sure, but still offering interest.

Michel Schneider Riesling Beerenauslese 1976, Germany — German beerenauslese wines, often called “BA” for short, are usually made from grapes affected by noble rot (botrytized grapes) and single berry picked. The colour in the glass, like most of the older sweet wines in the tasting, was orangey-brown, heading toward brickish. This was a wonderfully aged beerenauslese with a penetrating melange of compoted tropical fruits, toffee, and caramel. The fruits are more dried on the palate and the caramel/burnt brown sugar notes more pronounced. It was creamy and luxurious and the finish long and somewhat lifted.

Oremus Tokaji Aszu 5 Puttonyos 1988, Tokaj, Hungary — So, Aszu means botrytised grapes and 5 puttonyos means 120 g/l of residual sugar or more. This was still developing on the nose with notes of dried apricots, honeycomb, caramel, and peach preserves. Not as honey sweet as the wines above, but still high RS with fleshy ripe apricots, yellow apples, a creamy texture, roasted almonds, and a long, luxurious finish.

Hidden Bench Vidal Icewine 2005, Beamsville Bench, Niagara — 2005 was the first full commercial vintage at Hidden Bench and what a treat to have this is the tasting. The nose is intense and penetrating with ripe apricots, peach and citrus preserves, honeycomb, and mineral notes. Such lovely, honeyed notes on the palate, a plush texture, figs, marmalade, and still enough finesse to keep it interesting through the finish.

Lornano Vin Santo del Chianti Classico 1999, Tuscany, Italy — Tuscan Vin Santos are uniquely made. After harvesting, the Trebbiano and Malvasia grapes are dried for a few months, either on racks or dangling from ceilings, so that the sugars become concentrated. A slow fermentation follows, then the wine is aged for a decade or more in wooden barrels before being bottled. It shows a deep, golden colour in the glass with a savoury, sweet brown sugar nose that amplifies the sultana raisins, toffee, subtle mint, apricot jam, stewed citrus, and baking spices, It’s highly concentrated on the palate with a creamy, unctuous texture, slight oxidation, and layers of over ripe apricots, peach preserves, marmalade, toasty almonds, and super sweet honey notes that’s all somewhat tempered by the softening acidity.

Bruno Sorg Vendange Tardive Tokay Pinot Gris 1999, Alsace, France — Vendange Tardive is a classification for Alsace wines signifying a late-harvest wine with a greater-than-usual concentration of natural sugars, which is the result of the grapes having achieved minimum required ripeness levels (the top producers consistently exceed these). There’s only one level higher, the rare sélection de Grains Nobles, French for “selection of noble berries” and refers to wines made from grapes affected by noble rot. This was my modest contribution to the tasting and one I was worried about because the bottles in the past have been hit and miss. Fortunately, this was one of the better ones and showed more freshness with floral notes to go with citrus, ginger, apricot tart, and nectarine. Not as much depth and honey sweetness as some of the others in this tasting but definitely more freshness and finesse on the palate with notes of poached pear, honeycomb, dried apricot, ginger and still tingly acidity on the finish.

Dr. Loosen Riesling Icewine 2016, Mosel, Germany — What a rare treat from the icon Ernie Loosen. Icewine in Germany is generally picked without any botrytised grapes, but Loosen is unique in that it allows noble rot to develop for 15-20% of the grapes used for his icewine. This was clean and bright on the nose with lovely savoury/floral notes, passion fruit, citrus peel, and peach preserves. So balanced on the palate with harmonic and ripe orchard fruits, lime, passion fruit, tropical fruit accents, and sweet honey notes that are nicely balanced with the firm vein of acidity. Such a baby right now with the stuffing to improve for decades.

Jose Maria da Fonseca 25 Year Old Moscatel de Setúbal, Portugal — After researching this wine, I discovered the dessert wine of Setúbal, made of the varieties Moscatel and Moscatel Roxo, is one of the oldest and most famous sweet wines in the world. Well, count me totally out of it. This is absolutely the first I have seen or even heard of this incredibly delicious treat. This unique fortified sweet wine is blended from multiple vintages, where the youngest wine is often at least 20 years old and the oldest is nearer 80 years old. The key difference between Moscatel de Setúbal and other fortified wines is the winemaking process after vinification. As with almost all sweet, fortified wines, pure grape spirit is employed to stop fermentation (a process known in France as mutage), and the wine is then aged for a period in wooden barrels. Setúbal winemakers add the leftover, highly aromatic Moscatel grape skins to the mix and allow them to macerate with the wine for as long as six months. This gives Moscatel de Setúbal its intensely pungent, floral aroma. While Redelmeier’s bottle says “25 Year Old” on the label, he’s also been aging it in his cellar for another 25 years. It had the most intense nose in the tasting with maraschino cherries, a subtle pungent floral note, sultana raisins, toasted almonds, caramel/toffee, and Christmas cake spices. The luxuriously textured palate is dripping in honey, dried apricot, toffee, roasted nutty notes, dark chocolate, and rich spice notes with an echoing finish.

Graham’s Vintage Port 1977, Portugal — Sticking with the fortified sweet wines in the tasting, we moved on to a pair of Vintage Ports from two different decades. The Graham’s has an earthy entry with dried red berries, figs, macerated cherries, cocoa, and sweet Christmas spice notes. There was some evident heat on the palate but still revealing a full-throttle fruit attack of compoted red berries, plums, figs, blackberry jam, silky tannins and long, long, lingering finish.

Dow’s Vintage Port 1994 — The 1994 Vintage Port is one of the most highly scored and celebrated Port vintages ever. The Fonseca and Taylor Fladgate Ports both received 100 points and were jointing awarded wines of the year in the Wine Spectator magazine. I can remember lining up in the middle of winter outside a Vintages store in Ottawa to get my allotment of two half bottles of each of the wines. Now they command prices far out of reach of normal people like me. To try the Dow’s from Redelmeier was a treat. It’s a much different expression of Port with a prominent floral, almost minty note on the nose but evolves to show jammy cassis, blackberries, dried tobacco, earthy notes, and toasted vanilla. It’s rich and decadent on the palate with earthy/savoury notes, mulled dark berries, figs, kirsch, and licorice all delivered on a highly structured bed of tannins and a long, echoing finish.

D’Oliveiras Madeira Boal Reserva 1977 — The founders of D’Oliveiras were visionaries who saw the true value of Madeira wine and its ability to improve over time. They began storing as much Madeira as possible, letting it slowly mature inside the barrels for future generations to be able to enjoy it further. For that reason, D’Oliveiras is the only Madeira wine company that owns Madeira bottles and barrels from as far back as the 1850’s that can still be commercially purchased. Madeira wines are considered some of the longest lasting wines on Earth. It has an intense nose of tangerine zest, dried fruits, leather, toffee, Espresso bean and toasted almonds. It’s remarkably balanced on the palate with a smooth entry that reveals candied citrus, a full range of dried fruits, mocha notes, toffee, orange zest and a super long and lifted finish. A beautiful wine to finish a remarkable tasting.

An impromptu tasting that

digs deep into Bench terroir

The tasting at Southbrook was emblematic of what happens at wineries all over Ontario as winemakers try to avoid the dreaded cellar palate and keep putting their own wines up against the best in the world. One such winemaker is downright obsessed with not only judging his Niagara wines against the best Burgundy has to offer but also comparing sub-appellation wines and single vineyard expressions to better understand the soils of Niagara and what it imparts. His name is Thomas Bachelder, owner/winemaker of Bachelder wines and winemaker at Le Clos Jordanne.

A funny story happened this summer that points somewhat to the obsession Bachelder has for endless tasting and learning. It was a warm June day, and I was just pulling out of Cloudsley in my SUV after a tasting. Travelling north on Victoria, my cellphone rings. It’s Bachelder, and he’s right in front of me in his pickup. “Listen, I know it’s last minute, but do you want to taste some Pinot Noirs.” First of all, what???, you are right in front of me? Secondly, of course I want to taste some Pinots. “OK, can you host at your house,” he asked me. Not an hour later, Bachelder, Niagara College faculty professor of wine programs, Peter Rod, and Kelly Mason, winemaker/owner of Mason Vineyards and winemaker at Queylus are on my back porch to blind taste 12 different vineyard expressions of Pinot Noir from the Niagara Bench.

The point of the tasting, that included different producers from single vineyards on the Bench, was to drill down to ascertain what makes them unique and can a case be made for elevating key vineyards in the region to an elite status.

It’s a long process, and an important one, with real potential to learn more. One major takeaway from the back porch tasting: Niagara can produce some awesome Pinot Noirs across many producers and terroirs that are all unique in their own way. It’s defining what those differences are over many vintages that will determine what makes each one special. This wasn’t a tasting about producer, it was more about where they come from.

The wines we tasted that day were Leaning Post Senchuk Vineyard Pinot Noir 2019, Hidden Bench Felseck Vineyard Pinot Noir 2019, Hidden Bench Locust Lane Vineyard Pinot Noir 2019, Cave Spring Pinot Noir 2019 (Cave Spring Vineyard), Malivoire Mottiar Vineyard Pinot Noir 2019, Mason Vineyard Pinot Noir 2019, Tawse Cherry Ave. Vineyard Pinot Noir 2019, Cloudsley Cellars Hanck Vineyard Pinot Noir 2019, Bachelder Wismer-Parke Vineyard Wild West End Pinot Noir 2019, Le Clos Jordanne Le Grand Clos Pinot Noir 2019, The Farm Neudorf Vineyard 2019, and a ringer tossed into the mix to keep us all honest, the Louis Jadot Savigny-Lès-Beaune Clos des Guettes 2019.

We all took notes of the tasting before Bachelder revealed what the wines were, but the challenge was finding descriptors that were less about fruit and spice attributes and more about what made the wine unique. That usually came down to minerality, finesse, and the intangibles. Descriptors like savoury, stony, saline, salty, bloody/iron, soft/structured tannins, reductive (but even that can be winemaker style), elegant etc.

Bachelder has the full spectrum of commonality between the four tasters’ notes as his quest continues.

It’s not just wine tasting …

One final note, while most of these impromptu tastings can involve international wines, neighbour’s wines, Canadian wines, old or young, or a combination of all the above, they don’t even have to just wine.

One of the more eclectic tastings I was at was a dizzying array of 30+ sample tasting of ciders from around the world, again organized by Bachelder and held at the Bat Cave on Locust Lane.

About 12 of us gathered get a feel for the various styles being made mostly outside the borders of Canada. It was a stunning tasting with myriad styles — from fresh and fruity, to funky and reductive, to complex and age worthy. We weren’t there to shine a light on the relatively short history of ciders in Ontario and Canada, but it certainly pointed to a lack of a consistent style across the board domestically.

Most successful cider regions work with apples specifically grown for the singular purpose of making cider, while Canadian cideries are generally working with apples grown primarily for eating. In today’s world of cider locally, far too many cideries, in my opinion, are focused on flavoured ciders and hybrids rather than interesting ciders from the correct apples. There just doesn’t seem to be the impetus from farmers to plant the kind of apple trees needed for a thriving and serious cider industry.

That was my takeaway from the tasting.

Comment here