I am a Canadian wine drinker. Yes, I drink Canadian Riesling, Cabernet Franc, Pinot Noir and Chardonnay, that’s a given, but L’Acadie Blanc, Léon Millot, Marechal Foch and even Zweigelt all find their way into my glass from time to time. Hell yes, I am Canadian and I never discriminate, so if I see a Nebbiolo, Corvina, Rondinella, Molinara or anything appassimento, fill me up. I am nothing if not polite, because I am Canadian.

I am a Canadian wine drinker. Yes, I drink Canadian Riesling, Cabernet Franc, Pinot Noir and Chardonnay, that’s a given, but L’Acadie Blanc, Léon Millot, Marechal Foch and even Zweigelt all find their way into my glass from time to time. Hell yes, I am Canadian and I never discriminate, so if I see a Nebbiolo, Corvina, Rondinella, Molinara or anything appassimento, fill me up. I am nothing if not polite, because I am Canadian.

I’m not a lumberjack or a fur trader. I don’t live in an igloo or eat blubber (yuck!) or own a dog sled (well, I did once). But I certainly know what I like to drink. And as I travel across this great land of ours, I drink whatever is put into my glass and I quaff heartily. And I (usually) like it.

I speak English and a little French but not American. I pronounce meritage like a French word even though it’s a California thing and rhymes with heritage. I believe in diversity, not assimilation, and that the beaver is a truly proud and noble animal.

Canada is the second largest landmass, the first nation of hockey and the best part of North America. My name is Rick, I am Canadian and I drink Canadian wine.

And (with my sincerest apologies to Molson Canadian) I have absolutely no clue what Canadian wine means.

Canadian wine? That just confuses me.

As a young man I was weaned on Canadian wines that, as it turns out, weren’t that Canadian at all. Some of them still aren’t. In fact most “Canadian” wines made today aren’t Canadian at all. That’s a very sad statistic, to be sure. International Canadian Blend (ICB) wines represent 73% of all Ontario wine sold and accounts for more than 54% of the grape crop, according to the Winery and Grower Alliance of Ontario (the percentage is similar in B.C., according to Constellation Brands, the U.S. owner of Inniskillin and Jackson-Triggs). These are wines made with bulk fruit from anywhere but Canada and blended with a minimum of 25% domestic fruit in Ontario or as little as 0% domestic fruit in B.C. Vintners Quality Alliance wines (VQA) account for only 27% of volume sales and 46% of the grape crop in Ontario alone.

As a young man I was weaned on Canadian wines that, as it turns out, weren’t that Canadian at all. Some of them still aren’t. In fact most “Canadian” wines made today aren’t Canadian at all. That’s a very sad statistic, to be sure. International Canadian Blend (ICB) wines represent 73% of all Ontario wine sold and accounts for more than 54% of the grape crop, according to the Winery and Grower Alliance of Ontario (the percentage is similar in B.C., according to Constellation Brands, the U.S. owner of Inniskillin and Jackson-Triggs). These are wines made with bulk fruit from anywhere but Canada and blended with a minimum of 25% domestic fruit in Ontario or as little as 0% domestic fruit in B.C. Vintners Quality Alliance wines (VQA) account for only 27% of volume sales and 46% of the grape crop in Ontario alone.

So, yes, it’s confusing. And it gets more so.

In Ontario and B.C. there are VQA wines, non-VQA wines and those blended wines mentioned above. VQA means they are wines of origin and represent a promise of quality and authenticity, according to VQA. A bottle stamped with VQA is supposed to ensure precise adherence to rigorous winemaking standards and that label integrity has taken place. It’s meant to be a message for consumers that they can trust that these are authentic Ontario or B.C. wines.

Which isn’t practical or achievable in other wine regions of Canada and thus not wanted.

In Nova Scotia, for example, the growing season is shorter and cooler and not kind to vinifera grapes, the very grapes VQA has embraced; you know, the noble ones such as Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Riesling, Cabernet, etc.

So Nova Scotia has embraced a wide selection of hybrid grapes (most of which Ontario and B.C. dug up and replanted long ago in favour of vinifera) and has built a thriving wine industry around those grapes. L’Acadie isn’t a swear word in Nova Scotia, it’s a staple of the wine industry and produces some stunningly delicious wines that help give that region its identity.

So Nova Scotia has embraced a wide selection of hybrid grapes (most of which Ontario and B.C. dug up and replanted long ago in favour of vinifera) and has built a thriving wine industry around those grapes. L’Acadie isn’t a swear word in Nova Scotia, it’s a staple of the wine industry and produces some stunningly delicious wines that help give that region its identity.

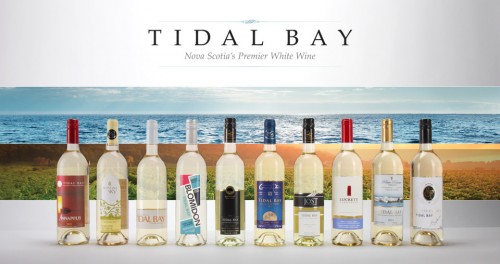

It has rejected VQA rules and written its own credo that has been embraced by many wineries in the new Tidal Bay appellation.

The wines there must follow the same set of standards, which includes making the wines with the four “base” grapes of L’Acadie Blanc, Seyval Blanc, Geisenheim 318, and Vidal making up 50% of the blend. The distinctive taste profile is made to reflect the classic Nova Scotian style: lively fresh green fruit, dynamic acidity and characteristic minerality.

Simon Rafuse, winemaker at Blomidon Estate Winery and shown above, says: “We’re starting to develop a bit of a Nova Scotia wine culture, slowly but surely.”

Simon Rafuse, winemaker at Blomidon Estate Winery and shown above, says: “We’re starting to develop a bit of a Nova Scotia wine culture, slowly but surely.”

But how that even remotely translates to a Canadian identity, well, that’s another matter entirely.

“I’m not sure the average Nova Scotian has a clue what’s going on in the Ontario and B.C wine industries, or that Quebec even makes wine,” says Rafuse. “Sadly, our provincial borders make it difficult for us to access anything but the most mass-produced wines.

“I would love for there to be a national wine identity, and for someone in Whitehorse to be able to start a meal off with some Nova Scotia bubbly, have an Ontario Chard with the appetizer, a B.C. Syrah with the main, and a Quebec Ice Cider with dessert. But until we de-regulate the system and make Canadian wines accessible to people across the country, I think the best we can hope for are strong regional wine identities,” Rafuse says.

“I would love for there to be a national wine identity, and for someone in Whitehorse to be able to start a meal off with some Nova Scotia bubbly, have an Ontario Chard with the appetizer, a B.C. Syrah with the main, and a Quebec Ice Cider with dessert. But until we de-regulate the system and make Canadian wines accessible to people across the country, I think the best we can hope for are strong regional wine identities,” Rafuse says.

I suppose that If the Canadian wine industry had started in the 6th century BC, like the French, we might be pigeon-holed into a few mandated grapes, or segregated into regional styles, not unlike Burgundy (Pinot Noir, Chardonnay) or Bordeaux (Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Petite Verdot, Malbec, Cabernet Franc). But with barely 30 years under our belts (some say the modern wine industry in Canada really got going In 1988 when free trade with the U.S. began and the establishment of VQA), we are really just at the starting gate to finding that elusive identity.

Canadian wineries are well aware of the dangers out there: Think Australia and Shiraz, New Zealand and Sauvignon Blanc, Argentina and Malbec. All lovely grapes that make lovely wine, but when the popularity of any one of those wanes, what are you left with? Each of those countries is now struggling to get the world to think beyond their one-trick-pony reputation. It’s just not easy to do.

Winemaker Dwight Sick, in above photo taken by Stuart Bish, from Stag’s Hollow Winery in the Okanagan Valley, scoffs at the notion of a Canadian identity. He even snarls at a B.C. identity.

Winemaker Dwight Sick, in above photo taken by Stuart Bish, from Stag’s Hollow Winery in the Okanagan Valley, scoffs at the notion of a Canadian identity. He even snarls at a B.C. identity.

Growing Dolcetto, Tempranillo, Teroldego, Vidal, Grenache, Petite Verdot, Orange Muscat, among 10 other varieties of grapes, he says: “Yeah, crazy, I know, but like I said, if someone tells me I can’t do it, I usually do it anyway.”

A recent study in British Columbia points to Riesling and Syrah as the most likely signature grapes in that province, which prompted a barrage of negative comments from cynics. For Sick, “it just doesn’t make sense.”

He grows both those varieties, and makes some pretty nifty wines out of each, but “it’s detrimental to the industry to tell us what and where we can grow,” he says. “We are somewhat of a wild frontier. It’s about diversity and consistently producing a wide variety of styles of wines across the board.”

Like many, Sick dismisses the idea of a Canadian wine identity, especially in a country that doesn’t even have universal shipping of its own wines from province to province.

Like many, Sick dismisses the idea of a Canadian wine identity, especially in a country that doesn’t even have universal shipping of its own wines from province to province.

“What will set us apart is our ability to do many things well. Our identity is our lack of identity,” he says.

Lake Erie North Shore-based Gary Killops, who writes for his own wine blog Essex Wine Review, agrees with Sick that chasing a Canadian wine identity is pure folly.

“LENS is still trying to find it’s own regional identity,” he says. “That will come with time.”

Ontario’s southern most wine region has always existed in the shadow of the Niagara region, says Killops pictured left, but with new winemakers moving into the region, such as Colio’s Lawrence Buhler and Rori McCaw from Cooper’s Hawk Vineyard, the bar for quality wines in LENS has been slowly rising.

Ontario’s southern most wine region has always existed in the shadow of the Niagara region, says Killops pictured left, but with new winemakers moving into the region, such as Colio’s Lawrence Buhler and Rori McCaw from Cooper’s Hawk Vineyard, the bar for quality wines in LENS has been slowly rising.

“They both bring experience and have motivated other wineries to discover their own unique vineyard ‘somewhereness,’ ” he says.

Speaking of that new buzzword, ‘somewhereness’ is bandied about a lot in Ontario as winemakers focus and hone in on what they feel works best in the cool climate and soils in the various appellations around the province.

In Prince Edward County it is indisputably Pinot Noir and Chardonnay, in the emerging South Coast region, wineries are finding success by drying grapes in the abandoned tobacco kilns that once dotted the landscape there, but in Niagara, the largest wine producing region in Ontario, it’s not so simple.

Nowhere is the Canadian identity more fractured and divisive than in the country’s most recognized wine region. Niagara, much like the Canadian mosaic of ethnic diversity, is a Petri dish, a microcosm for the world’s palette of wine styles and varieties. Yes, terroir-driven Chardonnays and Pinots, thrilling and distinct Rieslings and Cabernet Francs, but also: dried-grape styles, Bordeaux blends, every Italian variety under the sun, fortifieds, sparkling, bio-organic, crazy blends, wild ferment, natural … nothing is off limits.

“As a relatively new wine region we have the freedom to experiment without the constraints of 400, 500 or 600 years history. We need to embrace this freedom and use it to our advantage,” says Hidden Bench Vineyards and Winery vigneron and proprietor Harald Thiel, pictured above. “Let’s revisit this question in 20 years when all the vines planted in the last 10 years are fully developed … could be very interesting.”

“As a relatively new wine region we have the freedom to experiment without the constraints of 400, 500 or 600 years history. We need to embrace this freedom and use it to our advantage,” says Hidden Bench Vineyards and Winery vigneron and proprietor Harald Thiel, pictured above. “Let’s revisit this question in 20 years when all the vines planted in the last 10 years are fully developed … could be very interesting.”

Thiel, who makes some of Niagara’s most vineyard-focused Chardonnays, Pinots and Rieslings, says the industry is far too young to have developed a specific identity.

“As an industry we are all pushing hard to improve vineyard and wine quality and market acceptance on an ongoing basis. Our identity might be one of continual improvement and experimentation to find our best varietals and best wines to be fully accepted by our domestic market.”

So, like I said, I am Canadian and I drink Canadian wine. But I’m not entirely sure what that means.

Note: This story originally appeared in Quench wine magazine

Comment here