By Rick VanSickle

I have never met Ryan Monkman, the introspective and fervid FieldBird Cider owner in Prince Edward County. But I sure want to.

Not just because the cidery and farm he and his wife Nicole own are crafting the kind of ciders that excite me, but also because of the passionate and honest way he deals with life through the eyes of man with vulnerabilities that he isn’t afraid to share. Through his various social media outlets, writings and interviews, Monkman is quick to put it all out there as he conveys his raison d’être for what he does and humbly heaping praise on those he loves and those around him who matter most to him.

“Fieldbird started because Nicole and I needed our children (Aspen and Linden) to see that it was OK to chase a dream. Even if we failed (and we still might),” he tells me via email. “The trying is the most important part. To not let a piece of yourself die. To keep trying when it’d be easier to quit. To run into a fucking wall a thousand times until the mortar starts to crack. To be different. To find something only you can add to this world. We’re not there yet, but we’re trying.”

It is his wife who is Monkman’s rock. “You also need to know about Nicole. That she pulls me daily through my struggles with PTSD. That she knits our family together. That she forces us to stay ‘us.’ Nicole never gets the credit for FieldBird; but it only exists because of her. She convinced me to quit my job and show Linden it was OK to chase dreams. She fuels our spirits and drives all the little bits that make FieldBird different. Nicole is the soul of FieldBird. I do the boring stuff. Without her, there’d be no FieldBird.”

Just imagine trying to open a new retail store in the middle of deadly virus epidemic? FieldBird had already made the bold step to vacate their previous retail outlet at Keint-He winery and open their own shop. When COVID-19 happened, the team changed gears and decided if they were to survive they needed to get a website with retail ordering and delivery built and running in a hurry to keep enough cash rolling in to pay some of the mounting bills and keep all employees on the payroll. In short order, the website was up and you can now order here. Monkman is eyeing a June opening for the new retail store, but that, like everything in life these days, is dependent on the coronavirus, flattening that damn curve and finding normalcy, such as it will be, in our lives.

If you haven’t tried FieldBird ciders you are in for a treat. It’s such an eclectic lineup of mostly still ciders (made like wines) and exciting sparkling ciders and perries with complexity and depth, all of which see some oak. He looks to his own palate for inspiration and still adheres to some wise advice imparted to him four years ago by Derek Barnett (Karlo Estate winemaker, also in Prince Edward County).

“The best lesson he gave me was to make something I would want to drink, so that’s what we do,” said Monkman. “Lots of oak barrels because, well, they’re fun. High acid apples because we eat fatty foods. Most of our ciders are still — that’s what Nicole and I like to drink. My dad, too.

“Last year, we launched our sparkling program. We make traditional method because it’s hard to do well; and that makes it fun. And we make ancestral method because my mom likes to drink it.”

As for his affinity for oak and not for flavoured ciders, he has two hard rules at FieldBird:

“Everything touches oak and no adjuvants (things like cherries, lemon peel, etc). Beyond that, it’s just selfishness. We’re new. We haven’t been selling for a while so I’m staring at a cellar full of cider that I might have to drink. At least I know Nicole and I will like it. My parents like it, too. I’m happy with that.

“We grow earth-friendly fruit, then stick it in barrel. We babysit each of those barrels for months. Testing, tasting, working, hoping. And then one day we blend on a whim.

“That’s how we make the cider.”

Another aspect of Monkman is his writing; he is prolific and writes voraciously late into the night. Some of his words make it onto the labels of his ciders, which are now crafted by Amelia Keating-Isaksen, formerly the talented winemaker at Morandin, and tell stories of how FieldBird ciders are born. To wit:

Easter. Sun woke at 6:17. Our perry slept. Dew rose and perry slept.

I raised the palate and opened the valve. Our perry rushed through the pipe in the filler. Hold. Body positioned. Perry rush. My hand grabbed the bottle and passed it downstream. Hand to hand, the capper plunged. Then capper to table to cage. Another bottle nested.

Easter awoke. Our perry did too.

Music plays louder when it doesn’t need to scream over a pump.

Failing a face-to-face tasting with Monkman, he reached out to get a selection of ciders in front of Wines In Niagara. Mike Lowe and I tasted through the ciders and we provide reviews below. I followed up with a series of questions for Monkman, who was kind enough to answer. This is a verbatim transcript of that Q&A.

Five Questions for Ryan Monkman

Wines In Niagara: You opened your retail store in the middle of a pandemic. What were the challenges of getting the store up and running and the impetus for launching it? How has it changed your life and that of your family?

Ryan Monkman: Last weekend, I dropped our two toddlers off at their grandparents’ house. I don’t know how long they’ll be there. Nicole (wife) and I are needed on the farm, and a sad reality is that tractors break. We need servicing and we need parts. We also need couriers to ship cider, and we handle fresh trees lovingly packed in damp mulch.

We stay home at night and stay at the farm during the day, but we’re not fully isolated like I wish we could be. Aspen, our youngest, is immunocompromised. We can’t risk bringing something home to him and we can’t risk having the farm fail. I miss Aspen blowing kisses and I miss Linden riding the tractor with me.

Now there’s no one to walk the orchard while singing Pete Seeger songs (Linden loves the “Oh-wee, oh-wye” in Arrange and Re-arrange). But I know they’re safer at my parents’ house.

Our life is different now than it was four weeks ago. Nicole and I are lonelier. Video calling isn’t the same as a post-nap snuggle. I have wonderful parents and there’s unbounded love between them and our boys. I know they’re safe. I know they’re having fun, but I’m heartbroken.

For the store, we’ve run it quietly since last fall. We closed in early March to protect our kids and our team. That was scary because we had no other way to sell cider.

We decided that we would keep any staff who wanted to stay. Surrounding ourselves with smart, kind people was the best move we’ve made. Things are bad right now, but they’d be worse without our team.

There was a week of awkwardness while each of our jobs changed. But then we figured it out. Nicole’s spent the last two days driving an excavator while building a website at night.

Mel has launched a blog about life at FieldBird and sharing our stories. Britt started selling by social media until the website was live. Then she taught us how to ship orders without fucking up. Derick has spent two weeks plotting and planting our new orchard with me. Joe has “self-isolated” in one of our tractors. Amelia, who took over the bulk of cidermaking last harvest, started running our business day-to-day while I’m planting and farming.

Half the team works from home and the other half stays far apart. That’s weird for us because a month ago we shared cake daily.

Our business is different than it was. Because of the team we have, I know we’ll be all right.

Mostly, though — what I think about at night — is that I miss my boys.

WIN: I was impressed with your ciders from the first time I tasted them at Keint-He winery. They really do appeal to a wine lover’s palate. What is your philosophy when you set about to create a cider for production? What kind of consumer did you have in mind?

Monkman: Four years ago, I was standing beside Derek Barnett (Karlo Estate winermaker, also in Prince Edward County) while he poured Chard for someone. I don’t remember who. And it might’ve been Pinot. Those details aren’t important.bDerek was asked if he liked his own wines. His response was simple: “If you don’t buy it, I gotta drink it.”

Derek helped us a lot when we started. He still helps us now. Derek taught us how to run a virtual and how to be home for supper. That being friendly was better than being a jerk.

The best lesson he gave me was to make something I would want to drink, so that’s what we do. Lots of oak barrels because, well, they’re fun. High acid apples because we eat fatty foods. Most of our ciders are still — that’s what Nicole and I like to drink. My dad, too.

Last year, we launched our sparkling program. We make traditional method because it’s hard to do well; and that makes it fun. And we make ancestral method because my mom likes to drink it.

We have two hard rules at FieldBird: everything touches oak and no adjuvants*. Beyond that it’s just selfishness.

We’re new. We haven’t been selling for a while so I’m staring at a cellar full of cider that I might have to drink. At least I know Nicole and I will like it. My parents like it, too. I’m happy with that.

*[In cider, adjuvants are things like cherries, lemon peel, etc.]

WIN: Tell me about how you make your ciders, where you source apples/pears, production in the cidery and the methods you use to create different blends and styles (still vs. effervescent vs. sparkling).

Monkman: There’s an orchard I love. It’s just north of Bloomfield on the left-hand side. I’ve walked this farm for three years. Our ciders are rooted in this soil. Every apple, every pear you tasted comes from this place.

In the orchard I love is a tree I love. For three years I’ve watched her. Bird’s nest in her in the spring, and then flowers erupt from her in May. Then as the summer wears on, apples pull her toward a living earth. She dances in the wind.

For two years I’ve dreamt of the place: how I could grow here, how it would grow me. How a bit of biodynamic love would let my favourite tree live healthier, live longer, and make better fruit.

Then one day we got lucky. The owner offered to sell us my favourite farm, and my favourite tree came with it.

That was a year ago. A year of planting flowers and building walkways. A year of putting in a new orchard and healing sick trees.

And it’s working. You’re not allowed to visit for a few months, but it’s working. The farm has new life. My favourite tree is thriving once again like it did years ago.

We grow earth-friendly fruit, then stick it in barrel. We babysit each of those barrels for months. Testing, tasting, working, hoping. And then one day we blend on a whim.

That’s how we make the cider.

WIN: Every label has a short inspirational story on it. Who does the writing and where does the motivation come from?

Monkman: Nicole draws our labels by hand and each vintage is a bird. 2017 was the Fieldfair. 2018 was the Orchard Oriole. 2019 is the Eastern Meadowlark.

My only job is to make sure the text honours her art. I fail at that more than I succeed. I figure you’re about to drink the bottle, so why bother telling you what to expect. Instead I want to tell a story. The stories are personal from our lives. Sometimes things I worry about. Sometimes people I love. Places I adore.

I want the reader to know us. They invited us into their home by buying a bottle. The label copy is a handshake. I’m limited in my ability, but I do the best I can. Anything less is an insult to Nicole’s drawings.

The process is tough. There isn’t much space on a label. I’ll write pages and pages, and then scratch down to five or six sentences. I never feel that my writing is good enough for Nicole’s drawings.

We started dating in high school when I lived in Ottawa and she lived in Calgary. I think I conned her into loving me by writing letters. If I don’t write well, she might realize how much more creative and brave she is than me.

And I miss deadlines often. I sit at Midtown (local brewery in Wellington) or my kitchen table and stare at scratched up pages covered in meaningless dribble. Often I cry when I write. Sometimes I laugh. Around the fourth kolsch, I’ll write something I can use.

Then each vintage I try again and each vintage I miss my deadlines.

In a few months we’ll release the first label I didn’t write. Our cellar hand, Mel, collected wild apples with her family and then fermented them in a tiny barrel. The cider is amazing and it’s completely hers. So Mel wrote the story on those bottles. It’s better than anything I’ve written yet.

WIN: What can you tell me the sparkling perry? I immediately fell in love with it, so pure, so sparkly and flavourful and different from every other perry I’ve tried. All your ciders are delicious, but this one is particularly amazing.

Monkman: Ria Windcaller lives in Massachusetts. I wouldn’t know her except she has a podcast called Cider Chat. I love Cider Chat.

After a year of listening, I decided to send her an email that we should meet. I asked her to take a road trip across Ontario with me. That was June of 2018. I drove her to a few of my favourite cideries like Garage D’or, Kings Mill, and Heartwood. On the second last day we went to the cellar at Keint-He. That’s where FieldBird lived at the time.

Ria and I talked about bâtonnage and steaming. We talked about stave thickness and barrel size. We also talked about forest location.

Ria asked if American Oak was good for cider. I said it wasn’t something we use, that the profile didn’t align. Then she asked if it could be used if that’s all someone had. I ranted for a while about the lack of tannin and that there’s too much lactone. I said how vile every cider I’ve had in U.S. oak was.

I don’t know why I reacted that way and it was wrong of me. I asked Ria not to use the recording and she generously didn’t. If you’re wondering, she still has it, so at some point I might have to give her a bribe.

I apologized to Ria but I was still wrong. I didn’t sleep that night. I felt guilty. I was right to feel guilty. I was a jerk to Ria and dismissive of an idea.

I know what it feels like to have a dream stomped on. I felt guilty because I was wrong.

The next morning, before meeting Ria for lunch, I placed an order. I called Radaux and had them build me a custom U.S. oak barrel.

I told Ria I was sorry again. For part of my penance, I would make the best perry I could and I would use a U.S. barrel. Perry is Ria’s favourite drink.

The barrel arrived in September on the truck with all of the other barrels. It was the first I unwrapped and the first I slapped a sticker with a name on, “Ria”. (We name all our barrels).

I only had enough pears to fill two barrels, so the blend is 50% new American oak. Primary fermentation took place in barrel, then aged on primary lees in those barrels for malolactic fermentation.

On bottling day, I blended the two barrels together, then added a bit of sugar to form bubbles in the bottle. And then the filler broke. So the perry went back into barrel and slowly chewed through the priming sugar.

We moved the barrels to our Bloomfield farm in April of 2019. On Easter morning, when I had free labour from my brother-in-law, we tried again (now third ferment). We bottled while listening to American folk.

If you’re wondering what makes it good, that’s simple. I fucked up and someone was generous enough to accept my apology.

Five FieldBird ciders to buy now

FieldBird Northern Spy Still Cider 2018 ($20, 89 points) — It shows a golden hue in the glass with an expressive nose of fresh apple, spice, orange peel, subtle and perfumed tropical fruits and a pretty floral note. Prepare for a jolt — the palate reveals a stark and austere cider, completely dry and bereft of effervescence, laid bare and wine-like with tart apple, underlying barrel spice notes and lemon/citrus accents on a textured, complex frame with a vibrant, tingling finish. I love that all FieldBird ciders are vintage dated, making them easier to cellar, which I would do with this just to coax a little bit of roundness and soften the sharp edges. I liken this to a perfectly dry, minerally Riesling, but with more apple than lime. Oysters anyone? Perfect.

Fieldbird Northern Spy 2017 Still Cider ($20, 88 points) – Medium straw in colour, the nose offers freshly crushed apple aromas with a delicate earthy note. It’s crisp and juicy on the palate, off-dry, and packed with fresh apple flavours. There’s a nice apple-skin tartness for balance and delicate fruit replays on the finish. This cider would be a good match with shellfish or a simple roast chicken. (Michael Lowe review)

FieldBird Golden Russet 2018 Still Cider ($25, 90 points) – This elegantly crafted cider pours bright, medium gold in the glass. It expresses floral aromas of apple blossom, bruised apple, and honey with a musky undertone. The palate is refined with vibrant apple and lemony citrus notes followed by a hint of yeast on the finish. It’s dry and complex with racy acidity and medium length. Pair with pan roasted fish with buttery sauces or pasta with cream sauce. (Michael Lowe review)

FieldBird Sing-Song Cider 2018 ($25, you have to ask for it as it’s not on the website, 90 points) — Made in the traditional method of sparkling wines with experimental varieties and finished at 10.5% abv. It’s essentially a brut nature, topped up with only itself, says cidermaker Amelia Keating-Isaksen, adding, it was aged en tirage for eight months before disgorging and bottling in November of 2019. It bursts with bubbles and shows a range of ripe/tart apples, lemon blossom, quince and leesy/bready/toasty notes on the nose. Searing acidity drives the boat on the palate with lovely fresh apple, zingy citrus in a dry, refreshing, vibrant style with lovely spice notes on the finish.

FieldBird Buzzing Chatter Still Cider 2017 ($15, 91 points) — This still cider is a barrel-fermented and oak aged blend of ambrosia and northern spy apples finished at 9% abv. The nose shows rich, broad bin apples, baked brown sugar with honey and spice accents. It’s zesty on the palate yet rich and saline with mulled apple, citrus accents, an earthy note and freshness through a vibrant, clean finish. Nicely balance between sweet/tart fruit.

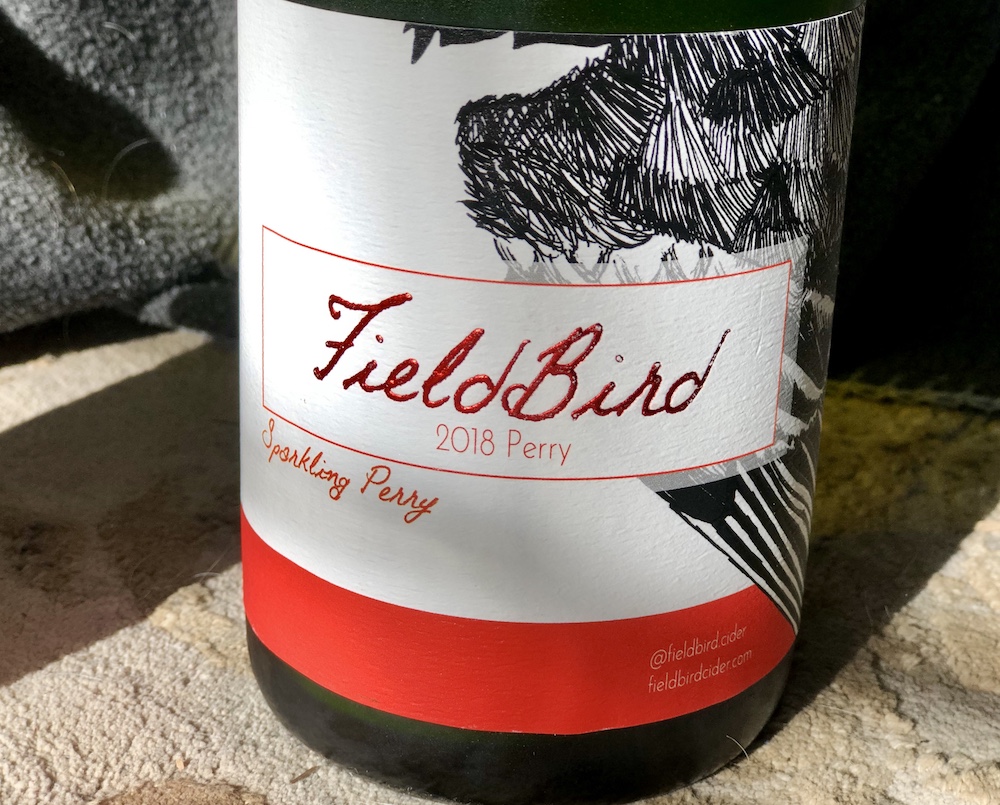

FieldBird Sparkling Perry 2018 ($30, 93 points) — Made with unknown pear varieties and finished at 9.5% abv. I adore this bottle-conditioned and perky pear cider; such a lively bubble that shows a cloudy hue in the glass and a hedonistic nose of pear tart, tinge of reduction, earth and lemon biscuit. It’s energetic on the palate and bursts with pear, apple skin and grapefruit that’s perky and vibrant in a dry, sharp, highly gulpable style. So delicious. Monkman explains the trials and tribulations making this cider:

“I only had enough pears to fill two barrels, so the blend is 50% new American oak. Primary fermentation took place in barrel, then aged on primary lees in those barrels for malolactic fermentation. On bottling day, I blended the two barrels together, then added a bit of sugar to form bubbles in the bottle. And then the filler broke. So the perry went back into barrel and slowly chewed through the priming sugar.”

Comment here