By Rick VanSickle

The Ontario wine industry is in one big hot mess right now, fighting fires on several fronts with few tools to extinguish all the flames engulfing them.

And if the industry fails to convince governments and their agencies (here’s looking at you, LCBO) to fix myriad problems they are confronting in the midst of a pandemic, many wineries will simply shut their doors forever. That’s the cold, hard reality right now.

“What we’re talking about is saving people’s businesses,” says an exasperated chair of the Ontario Craft Wineries (OCW) Carolyn Hurst, who is also co-owner of Westcott Vineyards in Niagara with her husband Grant Westcott. Hurst and her board members on the industry association that represents most VQA wineries in Ontario have been beating a path between Niagara and Queen’s Park trying to make anyone who will listen understand that wineries are in dire need of serious help both financially and from an image problem they say falls squarely at the feet of the government monopoly Liquor Control Board of Ontario.

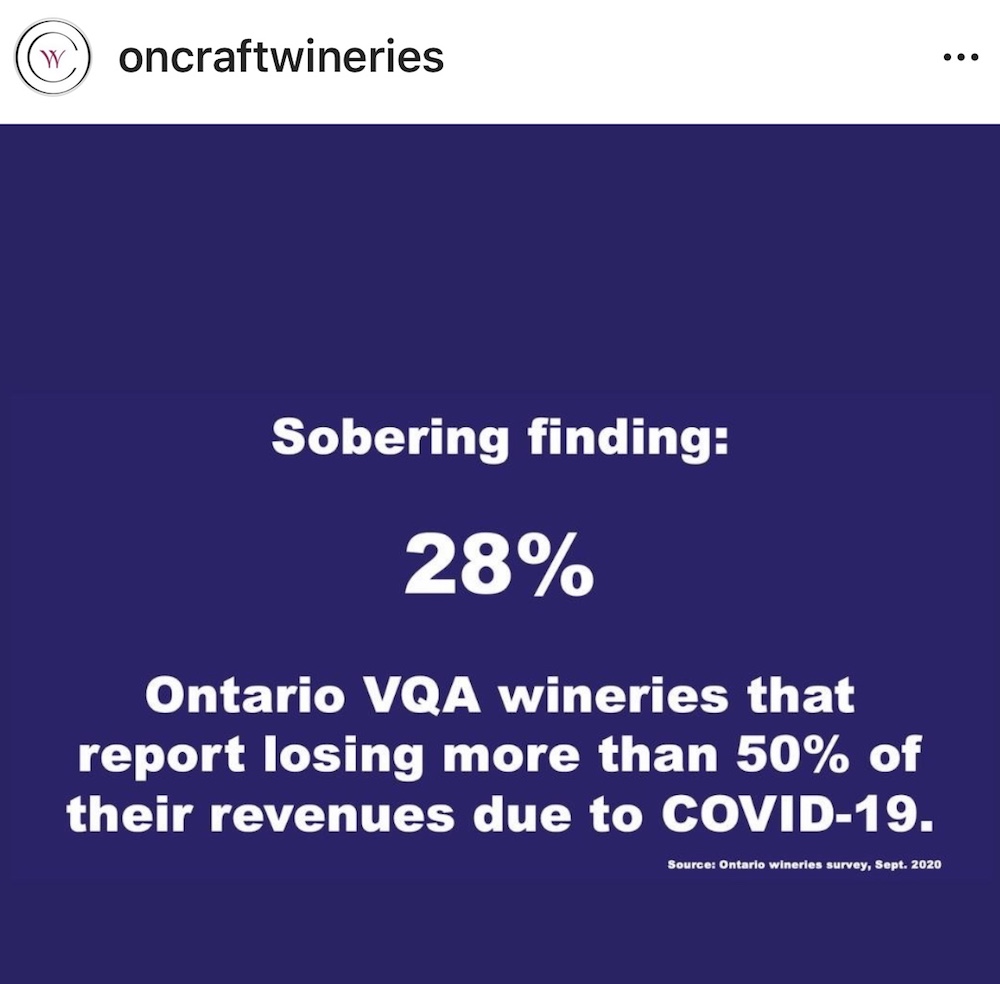

The financial woes are being piled on at a time when COVID-19 has put many wineries and growers on the edge of oblivion with substantial financial losses, rising expenses and grapes that will be left on the vine with no takers in a vintage that looks so damn promising.

Philosophical issues — namely the touchy subject of VQA vs. International Domestic Blends — has come back to haunt the industry and stir friction among the wineries that make only 100% VQA wines and those that make both VQA and International Domestic Blend (IDB) wines (under grand-fathered licences) that contain 75% juice from foreign grapes and a minimum of 25% Ontario fruit but look remarkably similar to Ontario wines even though they are sold, in theory, in a different section at the LCBO. It’s this issue — that seems the easiest to fix and the most puzzling of all the other issues — that is unnecessarily dividing the wine industry and it’s because the LCBO may or may not have changed the way they portray Ontario wines at their stores.

It you ask vice-chair of the OCW, Allan Schmidt, there is no debate on what’s going on. “It’s verified that they (the LCBO) want a unified message for IDB and local wines.”

The issue is in some displays at LCBO stores throughout the province that mix VQA wines with IDB wines on the same shelf under a VQA banner with the words like “100% Ontario grapes, 100% Ontario taste.” Some of the wines on the shelves are IDB, but some aren’t, which is confusing as hell for consumers and frustrating for VQA wineries, which are trying to run their businesses proudly using only Ontario VQA grapes. IDB wines can contain as little as 25% Ontario grapes and not exactly the cream of the crop of Ontario grapes. Much of content with international juice is blended in with the lower cost bulk grapes grown in Ontario by growers selling the produce at “plateau” prices. Those grapes are grown at extremely high yields, picked early with low brix and use very little labour during the growing season before being machine harvested. They are sold at 20% less than the base price for VQA grapes and end up in IDB wines mainly used by the two biggest producers Arterra and Peller for a wide range of wines either bottled under their own non-VQA labels or as standalone brands.

It all began, as far as anyone can tell, earlier this year around the time the COVID-19 pandemic began. The LCBO inexplicably changed the way it wanted to promote “Ontario” wines. Instead of separating the VQA wines from the IDB wines, like they have done now for many years while keeping them apart at LCBO stores, monopoly brass decided to promote them all as one entity.

When Hurst and others at the OCW realized what the LCBO wanted to do and protested, saying, “no, we are not on board with this marketing plan … they proceeded anyway,” said Hurst.

The OCW chair began to take notice when a display in a Burlington LCBO store spotted by her had mixed up wines under a 100% Ontario sign. Then other stores, notably in Niagara Falls and a large cluster in Ottawa also had the mixed products on display.

The LCBO responded to Wines In Niagara when asked about the display in Burlington, telling us it was an error by the management at the individual store and it would be fixed. As that was fixed, another problem arose and then it began proliferating with no explanation.

“Here we are, way down in the trenches, trying to get our products on the shelves properly,” says Hurst, and the message from the LCBO is: “They are doing their best (at the individual stores), but they have challenges, too, just getting the shelves stocked.”

Hurst says the OCW “has no problem with those wines (IDB) and what they are, they just need to be identified as to what they are. That’s not Ontario’s wine industry, that’s not what we need to do in our industry.”

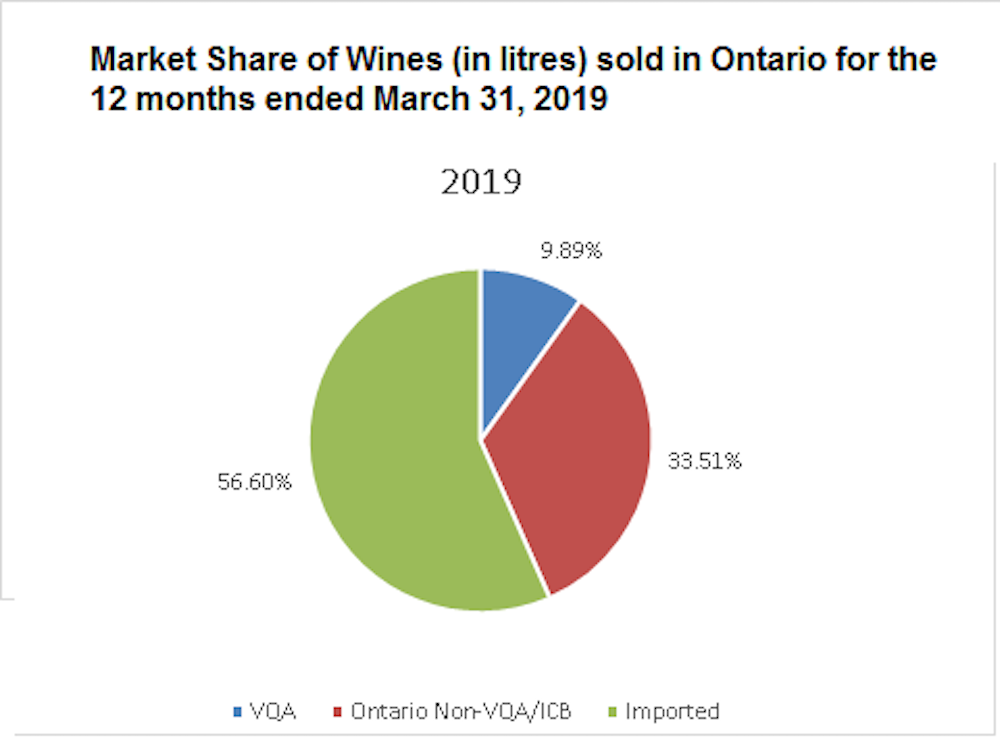

The problem is seemingly exacerbated by the fact that IDB sales are on the rise during the COVID-19 pandemic as consumers are drinking more but lowering their budgets, while VQA sales are flat or down. Even before the pandemic, Ontario non-VQA/IDB wines had 33.51% of the market at the LCBO with only 9.89% for VQA and 56.60% for imported wines (according to numbers by the Grape Growers of Ontario 2019 stats).

The shift in consumer buying habits comes at a time when Ontario wineries are hurting with added expenses due to COVID and falling revenue with a winter that will most certainly pile on more losses.

“At what point can we not do this anymore,” asks Hurst. “We have members just considering closing. It’s just a shame.”

Another point of view

Craig McDonald, vice president of winemaking at Andrew Peller Limited and responsible for all the wines, spirits and beer at Peller properties across the country, says the companies that have blending licences are being dragged into the debate over marketing at LCBO stores unfairly. “I’m on a bit of crusade to set the record straight,” he told Wines In Niagara.

He sees a different side of the debate.

“I do agree, it needs to be marketed as distinct. They do need to be kept separate,” he says, but during COVID, IDB wine sales are up at the LCBO and VQA is down. Consumers “are voting with their wallets. You can’t tell the consumer what to buy,” he says. “There’s a demand for the 25% component.”

McDonald says it isn’t his company, Peller, that is putting the confusing displays of IDB wines and VQA wines under the same banner, yet his company gets called out by some in the wine industry, and even by some who benefit when McDonald buys their unsold grapes, and dragged into the debate.

He refers to a photo Hurst took at the Burlington store of two Peller products that weren’t VQA products being promoted as 100% VQA. One of the boxes of wine was IDB and the other, the Chardonnay, was actually 100% Ontario. “The irony of all this is that that photo showed the good we’re doing in the industry.” While it didn’t say it was 100% on the box, because of packaging issues, it was all Ontario because of an aggressive program from McDonald and Peller to purchase surplus grapes in Ontario. When he over-buys surplus grapes in glut years, the Ontario content of those wines rise and growers get paid.

McDonald buys as much Ontario grapes (breakdown below) as he can in years when there is a surplus of unsold grapes (like 2020). “I always want to extend a hand,” he says, but “we rarely get the credit for buying the surplus from estate wineries and growers.”

Some of those grapes Peller buys are VQA, but when there is no more room in the VQA program at Peller and they just can’t sell or make anymore, it ends up in various IDB blends or 100% domestic, non-VQA wines, such as the boxed Chardonnay referenced above.

Over half of the grapes purchased by Peller in any given year, bought at plateau prices which is 20% less than VQA grapes, goes into IDB blends, which represents 33.5% of the market share of all wine sold in Ontario. VQA represents just under 10% of the market share.

For the 2020 vintage, Peller is buying 10,000 tonnes of Ontario hybrids from growers for IDB programs and hybrids/plateau grapes for 100% Ontario products (like the Chardonnay mentioned earlier). McDonald says there has been a “massive” increase in demand for value-priced wines since COVID.

Peller also harvests another 8,400 tonnes from estate vineyards and growers for all the VQA wines it makes.

“Think about the macro-economic impact to industry infrastructure if the IDB/100% programs get thrown out – or are put at risk financially with excessive tax lobbying from the industry it actually supports,” McDonald says. “I guess the key point is that the more affordable wines we sell (IDB and 100% domestic) far outweigh the demand for VQA. Since COVID, people are buying these wines in great numbers and I’d rather see them buy these than imports. Naturally, VQA remains at the top of the food chain but the consumer has shifted focus toward the more affordable category vs. premium, especially at the LCBO.

“If I didn’t have IDB, the industry would collapse. We can’t afford to lose a practice like that.”

McDonald, who feels the entire industry should be working together on the challenges ahead, instead of standing divided, says: “How do we get them (consumers) back onside with VQA when they go to the liquor board? It’s a real interesting time. I want to tell people the story, let’s talk to the industry first and then the consumer.”

‘It’s all wrong’

Listen, it’s of great concern to VQA wineries to see their hard work being compromised with LCBO displays lumping IDB and VQA into one category at some stores around the province.

As Hurst says: “It’s all wrong. The monopoly needs to put bottles on the shelves in the right place. It’s just not acceptable to do this.”

The LCBO has to own this and get it fixed. If it’s a concerted effort to lump IDB wines made with 75% juice from Chile, Australia or wherever, with 100% VQA wines, as Schmidt believes, just change course, educate your staff and return to the peaceful separation of VQA and IDB wines consumers came to accept just a few months ago. Now is not the time for this added aggravation.

Hurst says the OCW sent a letter to VQA to see if there are legal avenues to pursue, after all, VQA and 100% Ontario wines are protected under the law. As well, the president of the OCW, Richard Linley, has sent a letter asking members to be on the lookout for rogue displays around the province so he can point them out to the LCBO.

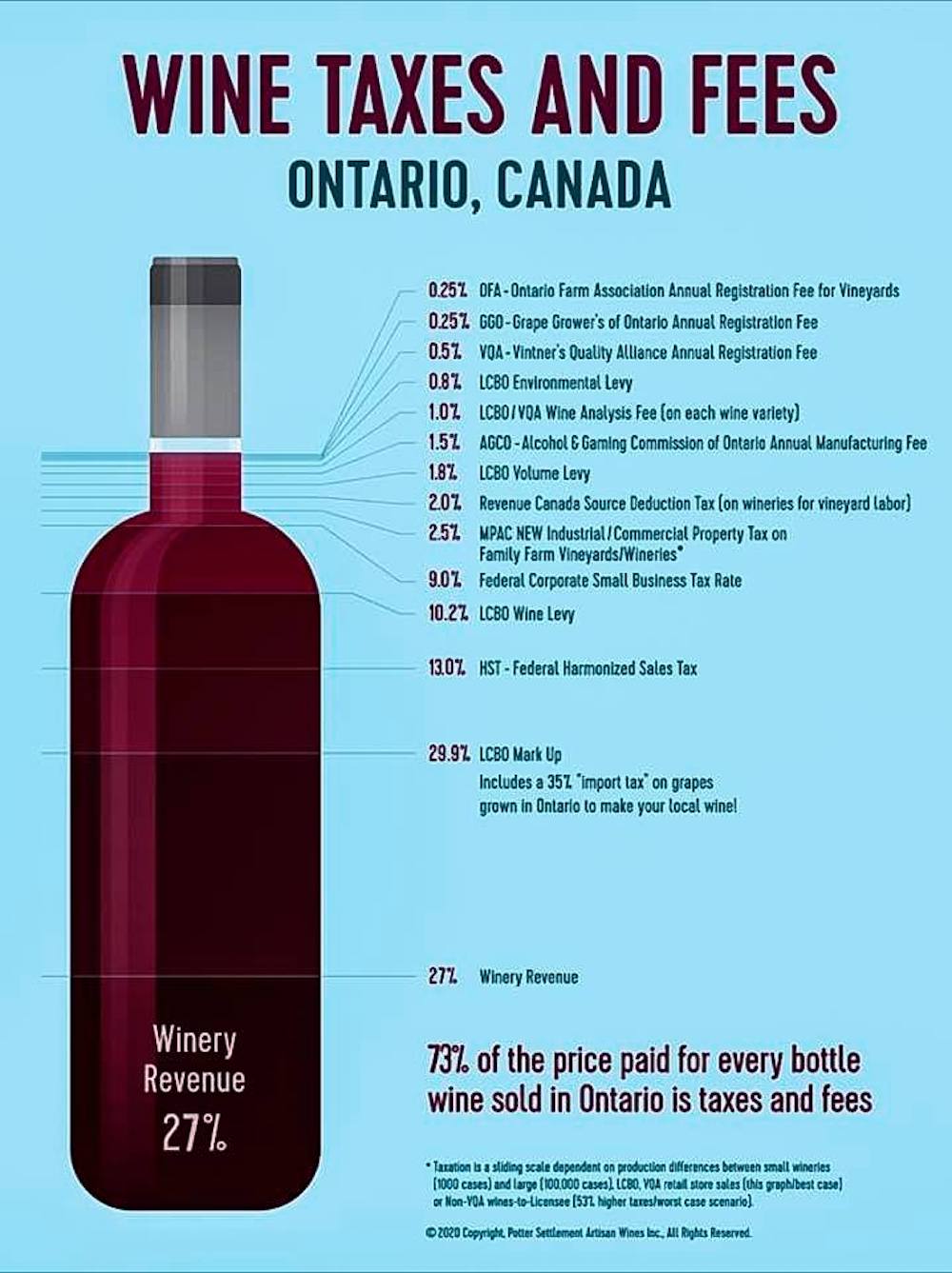

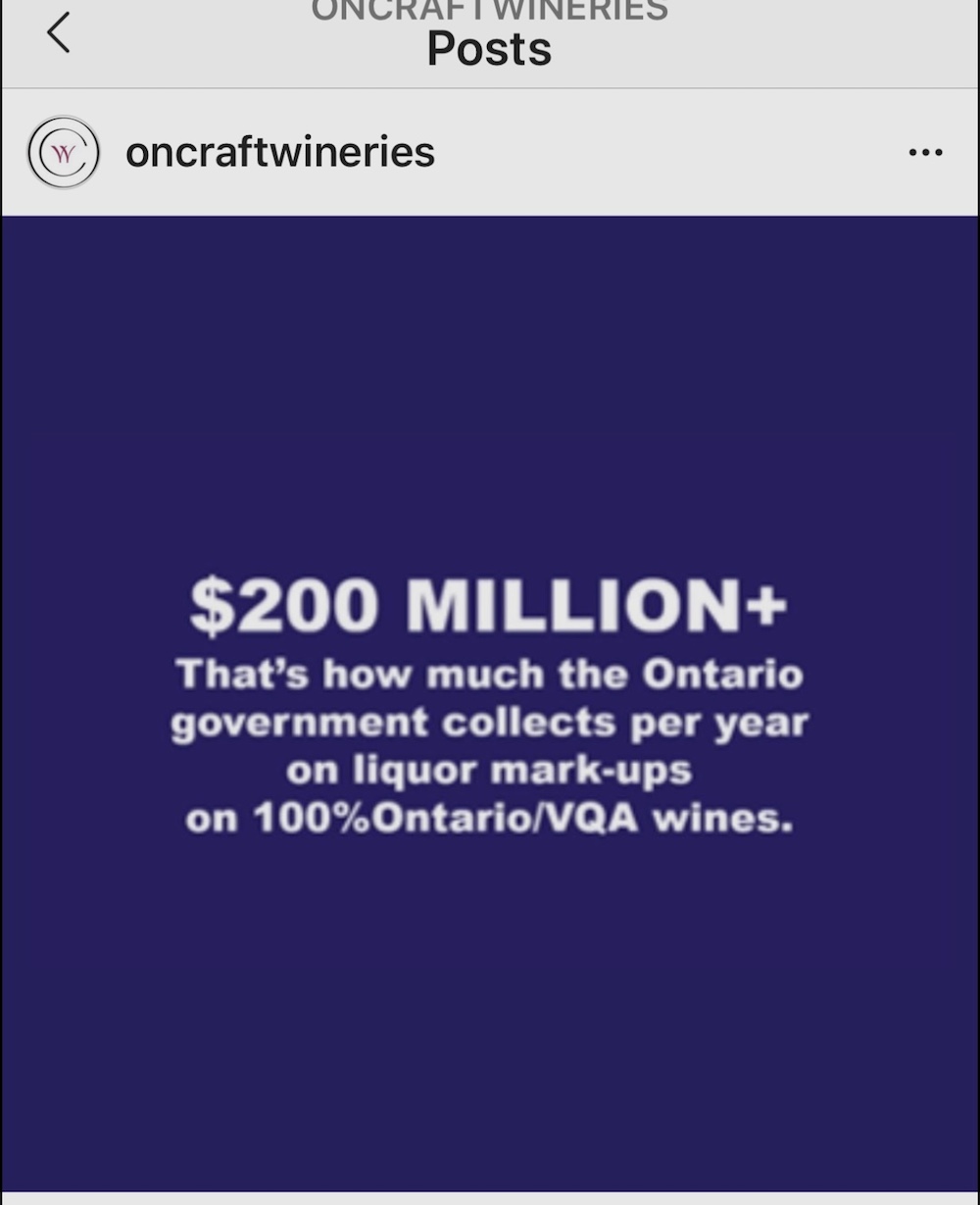

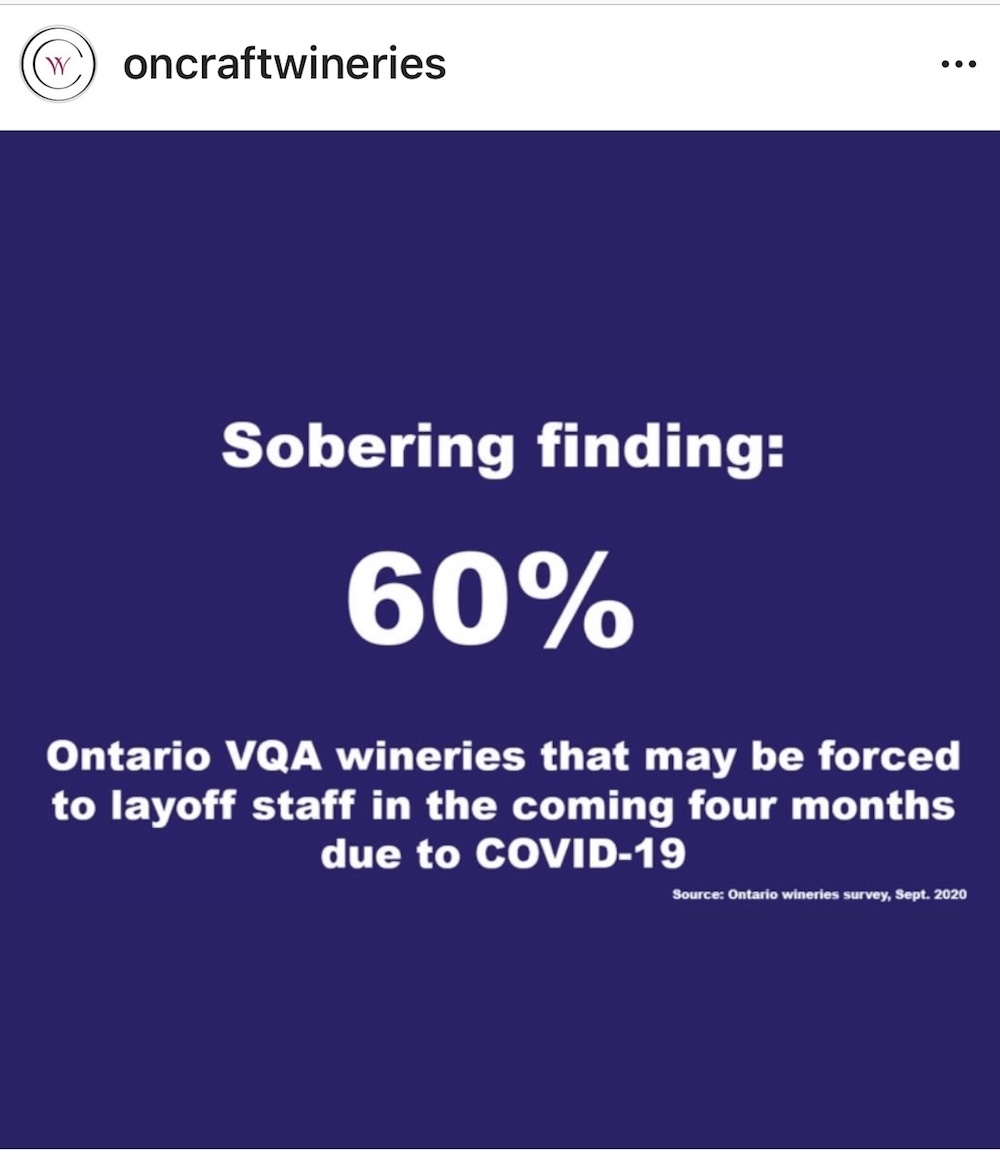

Meanwhile, an aggressive online campaign by the OCW points to many concerns of the Ontario wine industry. To wit:

That campaign is backed up by a petition consumers can sign here in support Ontario’s family-farm wineries.

According to the petition, “Ontario’s craft wineries are locally owned, family-farm businesses that create jobs, attract tourists, and support Ontario agriculture. Even before the COVID pandemic hit and tourism all but dried up, Ontario’s family-farm wineries were hurting – big time. All because of unfair taxes.

“For example, did you know that Ontario wineries are forced to pay a 6.1% tax per bottle of VQA wine sold at their own wineries to the Ministry of Finance — even when the government and other regulatory bodies play no role at all in selling?

“This unfair tax punishes local farm families for selling their own products on their own properties.

“Eliminating this unfair tax would help small wineries hire staff, invest in resources to provide greater experiences to their consumers, obtain new equipment for winemaking and retail operations, and more.

“As Ontario’s economy struggles to recover from the COVID crisis, Ontario’s craft wineries need tax fairness and relief now more than ever. Their ability to survive depends on it.

“Unfair taxes and outdated regulations were already hurting the wine industry, but coupled with the near shutdown of the economy, this is the biggest existential threat small wineries have ever faced.”

Nothing but a ‘sur-tax’

That 6.1% tax is nothing but a “surtax,” says Hurst. “There’s no service provided, it’s a straight tax. We are the highest value product being made in the country but we don’t get support and we’re taxed like no other business.”

Hurst says when Ontario wineries sell wine at the LCBO “we are treated just like an imported wine. We pay an import tax when we sell to the LCBO.”

Hurst maintains that if many of these issues facing the Ontario wine industry were addressed Ontario wines could double their market share to 15%, at least that’s the hope.

“We could be a bigger contributor. We can accommodate more tourism, sell more wine vs. imports and all the economic benefits would help the government generate more income. Our industry can do it. We can do it. But not by taxing us like nobody else gets taxed,” she says.

Some good news

A small bit of good news was delivered this week by the provincial government, one that could have an impact on Ontario wine.

The Ford government said it is committed to exploring options to permanently allow licensed restaurants and bars to include alcohol with food as part of a takeout or delivery order before the existing regulation expires.

“I think that this could be a wonderful opportunity for the Ontario wine industry to get more of our wines into the hands of Ontario consumers,” Hurst says. “The government has effectively created 15,000 more retail stores for wine, beer and spirits. COVID has exposed the fact that the restaurant industry was barely profitable. They have been taxed into oblivion as well. The next piece is getting to a wholesale pricing model that allows the restaurants to make some money on the sale without having to mark up on top of LCBO taxed level prices. We still have the same problem with domestic versus import — that we have to pay taxes that the imports don’t have to pay — even if we deliver the wine directly.”

What can you do?

It is a crucial time for the Ontario wine industry. As the industry tackles myriad issues on several fronts in the months and years ahead, consumers can do their part.

Sign the petition. Speak up when you see an LCBO display incorrectly displaying IDB wines as 100% Ontario. Make your voice heard and vote with your wallet.

And heed McDonald’s plea for industry players from all sides to get together, talk outside the confines of the boardroom and understand each other’s point of view and then have a unified message to take to Queen’s Park.

McDonald is a respected winemaker in Canada with numerous medals for the VQA wines he has made over the years. When he expresses an opinion on these weighty issues facing the industry, which he does sparingly, we should listen to what he is saying and try to understand another important point of view.

But, the “best way to support small Ontario wineries is to order directly or buy it there at the winery,” says Hurst.

Amen to that.

Great article, and well done getting both perspectives on this issue. VQA wines must be able to compete with IDB’s price points, otherwise marketing and shelf space are rendered moot points.

The import tax and the 6.1% levy, must go.

the LCBO and other taxation impositions make any wines over priced, wines sold in supermarket in the EU (mostly wine producing countries) are taxed by their government when we buy the bottle, why is there such difference as much as three time what we pay here in Canada, because it is replicated coast to coast. Please don’t tell me it is because of health care, the EU wine producing countries have similar healthcare system, the freight is low cost, the LCBO buys direct from producers over there and their agents are paid by the producers not the LCBO.

Ontario wines are much better than 30 years ago and i am old enough to be writing this.However the quality has also been improved on the imports, and Ontario is definitely noncompetitive because of high taxation.

This has contributed to a massive increase of home wine making, and any one will tell you that once you pass the learning curve they do produce descent drinkable wines at very low cost to them. The wine snobs will place their nose as high as they possible can up in the air and brush aside this comment. The LCBO marketing department studies the acceptability of the consumers and price it at the top of its acceptability. The exporters know that and play the same game. It will be raining frog before something favorable to the consumer happens!

Thanks for bringing this to light. Yes, as consumers we do need to vote with our wallets. Creating consumer confusion is essentially false advertising. Being lucky enough to live in wine country,I purchase direct from the wineries. Even if you don’t live close, with Covid-19, wineries have made it very easy to order direct. I vote by supporting craft wine.

The article misspells the word labelling, giving it only one L, the ugly American way.

Please correct the error.

Thanks.

i get the cry out of ON wineries but I also think they should do more to convince the provincial gment to reduce taxation on their wines…and also spend less on overwhelming luxury winery dwellings as they are some of the most outstanding architectural in ON. On average,a bottle of local wine should not cost more that 10$

so let’s blame an lcbo worker for being confused as to where something goes.

They put it in the wrong spot and all of a sudden it makes news?

Lcbo workers have also been working when others were not. During this pandemic, they have been struggling with lineups, rude customers and trying to keep everyone safe.

But let’s complain when a wine is put in the wrong spot.

Won’t buy from that winery. Sorry but the lcbo and the workers have NO say when it comes to consumers buying 4L casks since its cheaper and more convenient

Wow. And all this time I thought it was simply because VQWhatever wines were no better than imports and cost a heck of a lot more. Any industry that needs to have their product promoted above others while trying to convince the buying public it is ‘better’, when it’s really not, does not deserve this above and beyond promotion. The products should be able to compete on their 1) quality and 2) price.

Who is not being fair?

I’m sorry but for a reasonable price, I can buy a wine from the Puglia region of Italy that blows away any VQA or blended wine produced in Ontario. And Puglis is not even the best region in Italy! Ontario wine cannot place even against other Canadian regions like BC.

The 6 per cent tax has to go !!

Bon article. I always try to buy Ontario wines to my help my fellow Ontarians. Great products. And yes, one would hope that a PC government would look at the tax schemes and make it more fair for Ontario and Ontarians, regardless of the few millions in unfair taxes it receives. Premier Ford, de monopolise the LCBO. You will get back the same revenues later by letting flourish Ontario enterprises.

This article pointing out the mislabeling of signage of foreign imports as Ontario is systemic to the culture and mandate at the LCBO. For the first months of COVID 19 products from offshore were unreliable and LCBO shelves became empty. Meanwhile 100% local VQA ONtario wines were available. With a one in one out policy at the LCBO for VQA wines the portion of VQA sales at the LCBO is destined to never exceed the 7% of shelve space for VQA wines at the LCBO. The LCBO for whatever reason decided not to fill those empty shelves with VQA wines. As Canadians we need to ensure a domestic supply to keep imported wine prices down. Canadian production has a value add to the economy that imports do not, some 10 times the value of an imported product. This is jobs and taxes that in turn reduce Ontario taxpayers burden. Unfortunately the LCBO’s mandate is to purely earn tax dollars without the value add benefit to the economy. It would be safe to suggest that this error in mislabeling at the LCBO was is a regular error of convenience. You would never see an Australian wine being sold under a Product of France or USA section in the store. For someone to blame an employee is a stretch of the imagination as the public is often told by the LCBO that their employees are well paid and well trained. The solution is simple not just tax relief for domestic producers but as well to significant change the mandate of the LCBO to be promote and support 100% Ontario VQA wines.

In my opinion the issue here us the government allowing 2 giant wineries to have a different set of rules than the rest. The have been grandfathered into having their own stores (ie Wine Rack) and to be able to produce ICB wines. In the long run this has hurt the Canadian Wine Producers, except them.

The federal government has also bargained trade agreement with other countries giving them access at our markets and taxing Canadian grown and produced wines equally. Many of these countries have a subsidized industry.

Then there is the LCBO, who are training Ontario wine consumers that bulk Redwine at 17 grams of sugar is actually the standard in wine. Shame on them. Of course we can buy wine from Chile but not British Columbia.

Well done article on the current state of the ON wine industry. I think that the LCBO really needs to step up and be a driver in this situation in order for the province to see real improvements/changes in the 100% VQA wine segment. The Ontario wine industry today is a product of 100 year old prohibition laws that were not built to support local craft wineries and this obviously needs to change. The LCBO has been such a longstanding force in the province (and in the world) that can get people (exemplified in the above comments) who go around using Puglian wine as a comparison to Ontario..yeesh.

..and then after this ordeal we can work on cross-provincial selling 😅

Good article. Thank you.

I consider myself to be an informed Canadian wine nationalist. This doesn’t mean I am a qualified sommelier, nor that I drink Canadian wine exclusively; but that I know Canadian wines, I serve them 50% of the time (or more?) and I am qualified to claim they present value equal to or better that price – comparable international wines.

I have travelled to and worked in many places around the world and can state with certainty that local wines in every country I have visited are given extreme favouritism, relative to taxation, display, distribution and availability.

The “table & fine wine” industry ($12 – $70 per bottle) in Canada is +40 years old and considered to be well established at this time. This is not a flash in the pan and the industry makes a significant contribution to the national, as well as provincial economy. I cannot accept that +40 years of sustained quality and competitive presence doesn’t qualify this industry to receive the same preferential treatment as observed in its peer group of countries.

Canada, Nova Scotia, Quebec, British Columbia and Ontario deserve better leadership.