By Rick VanSickle

In a report commissioned by wine industry partners, the Ontario government and its antiquated LCBO monopoly takes the brunt of the blame for the stunted growth of VQA wines in this province.

Also in this extensive report, Southbrook Vineyards’ owner Bill Redelmeier offers analysis of both the Uncork Ontario and Vision 2030 reports and what needs to be done to propel market share for VQA wines.

It’s a detailed report by Deloitte titled Uncork Ontario and it concludes that the Ontario wine sector is well positioned to drive sustainable economic growth for the region, the province, and the country.

By following best-practices and implementing key policies, like those in leading global tourism economies and premium wine industries, this “Niagara Cluster” has the potential to drive at least $8 billion in additional real GDP over the next 25 years, the report reads. “This represents an uplift of roughly 35% above baseline estimates in the region.”

The Ontario wine industry plays a leading role within this cluster, acting as an accelerator for economic growth and job creation, the report maintains. Niagara is responsible for 90% of grape production in Ontario. In 2019, it is estimated the Ontario wine sector contributed just over $1 billion to Canada’s GDP.

“Ontario wines already compete and win on the global stage, so working together to turn Niagara into a world-class wine and tourism region to drive significant economic growth is within reach,” said John Peller, president of Andrew Peller Ltd. and Wine Growers Ontario member. “What’s required are supporting policies and best practices that both B.C. and leading global wine regions adhere to and where Ontario needs to catch-up.”

And therein lies the rub. The three associations that commissioned the report — Ontario Craft Wineries, Tourism Partnership Niagara, and Wine Growers Ontario — have launched a campaign to lobby the government for change to reach those lofty goals. But many factors would have to be enacted for the strategy to ever be successful.

Here are some of the key takeaways from the report:

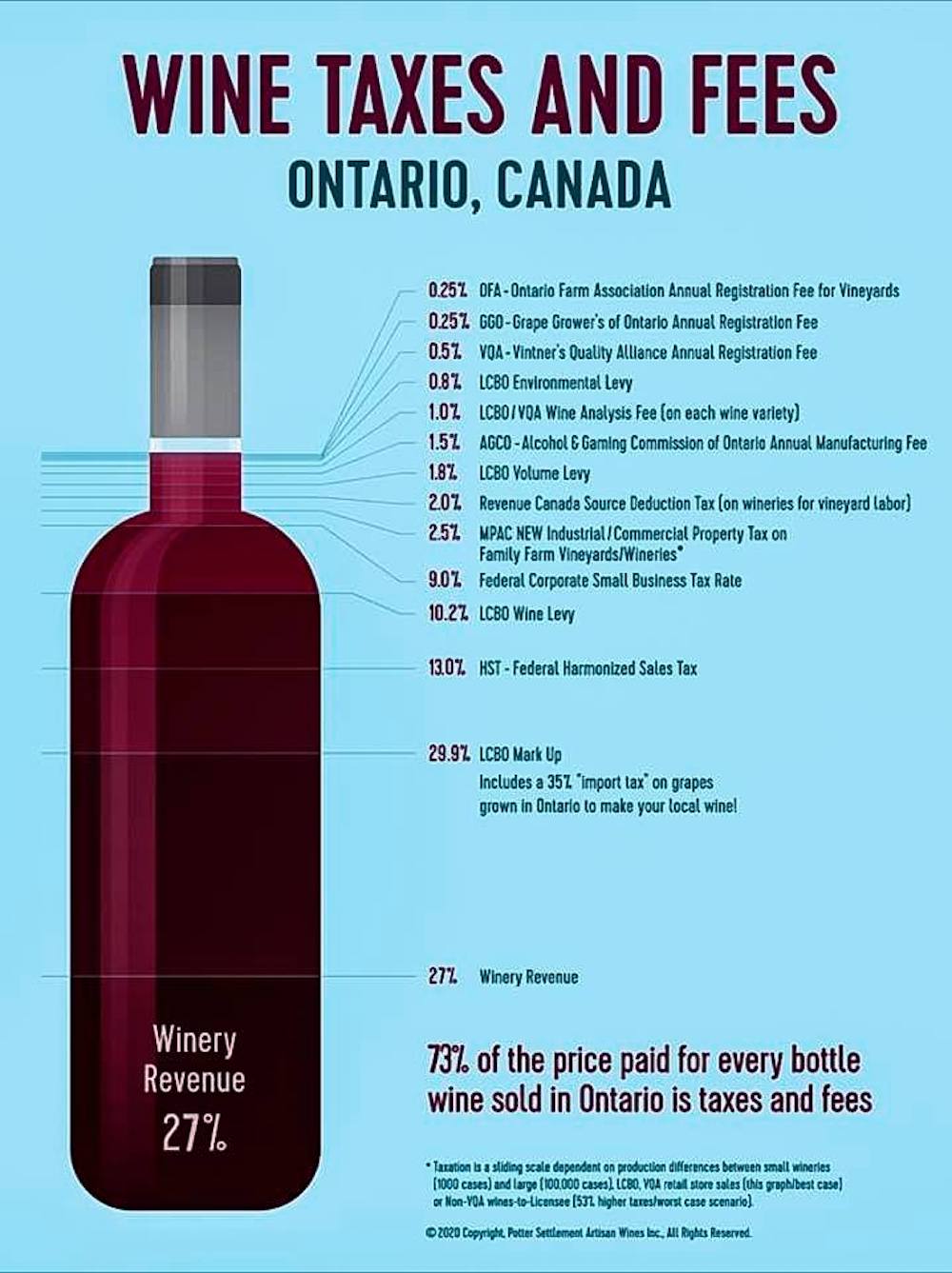

• The tax burden on Ontario wine is too high: Ontario’s wine industry is the most heavily taxed in the world. Ontario’s wine producers also don’t have direct delivery privileges in their own markets. What’s more, leading wine jurisdictions from around the world receive billions of dollars in subsidies.

• Retail expansion must be done right or else it threatens the future of Ontario wine and further supports heavily subsidized, foreign wineries: The GDP impact of a private retail model on domestic wine sales and tourism was estimated to be a negative $760M in GDP at year 10 after retail expansion, before indirect and induced effects.

• The LCBO holds the future of the domestic wine industry in its hands. It must make our domestic industry its priority—or stunt its growth: The market share for Ontario wines has remained relatively flat over the last 20 years. A major contributing factor is the lack of representation on LCBO shelves. If the Ontario wine’s market share by sales (33%) increased to that of B.C.’s market share (47%), it could provide $800 million in additional GDP over a ten-year period to Ontario’s economy.

“Now, more than ever, we need enhanced investment and supportive policies—prioritizing domestic industry, incentivizing investment, embedding best global practices—to achieve the level of growth, development and success enjoyed by Kelowna and other leading wine regions around the world,” the report said. “The key to realizing greater economic opportunity in the Niagara region is to remove existing barriers that only the Ontario wine industry faces.”

The report leaned heavily on comparisons to Canada’s other main wine region, the Okanagan Valley.

The contrast between Niagara and Kelowna is telling, the report pointed out. “Despite its steady sales growth over the last 15 years, Ontario’s wine industry lags significantly behind B.C.’s in terms of overall growth and stage of development. Between 2009 and 2019, Niagara’s real GDP grew by only 9.7% compared to Kelowna’s growth of 41.4%. At the same economic growth rate as Kelowna, investment in Niagara’s regional economy during those 10 years would have been an estimated $4 billion more, and real regional GDP $4.5 billion greater than the amount realized in 2019. Cumulatively, from 2009 to 2019, Niagara Region would have gained an additional $20.5 billion in real GDP. Increasing the Ontario wine sector’s share of the domestic market to equal B.C.’s could provide a cumulative $800 million in additional GDP to Ontario’s economy over a 10-year period,” according to the report.

Turing this around in Niagara’s favour is a daunting task. There are a lot of moving parts to navigate — especially at the provincial/LCBO level — before anything gets done in a timely way, but even a tweak here and tweak there will at least get the ball rolling in a positive direction.

The three groups that came together to commission the Uncork Ontario report — the Ontario Craft Wineries representing 100 VQA wineries across the province, Tourism Partnership Niagara, which plays a leadership role in tourism that helps to shape the regional narrative to attract business and leisure consumers to Niagara, and the Wine Growers Ontario, whose members represent over 80% of all of wine made in Ontario including 100% Ontario (VQA) and International Domestic Blends (IDB) — have found common ground in their fight for greater prosperity from what the wine region can provide with a sea change in government regulations, especially when it comes to the LCBO.

However, it’s not a level playing field for all three of the entities above. Ontario Craft wineries might represent the majority of VQA wineries in the province, but they have more to lose and more to gain than the Wine Growers Ontario, which holds the majority of the power. The growers’ association represents the largest wineries in Ontario, such as Arterra, Peller and Magnotta, who also have grandfathered licences to make non-VQA wines from imported grapes and operate independent wine shops.

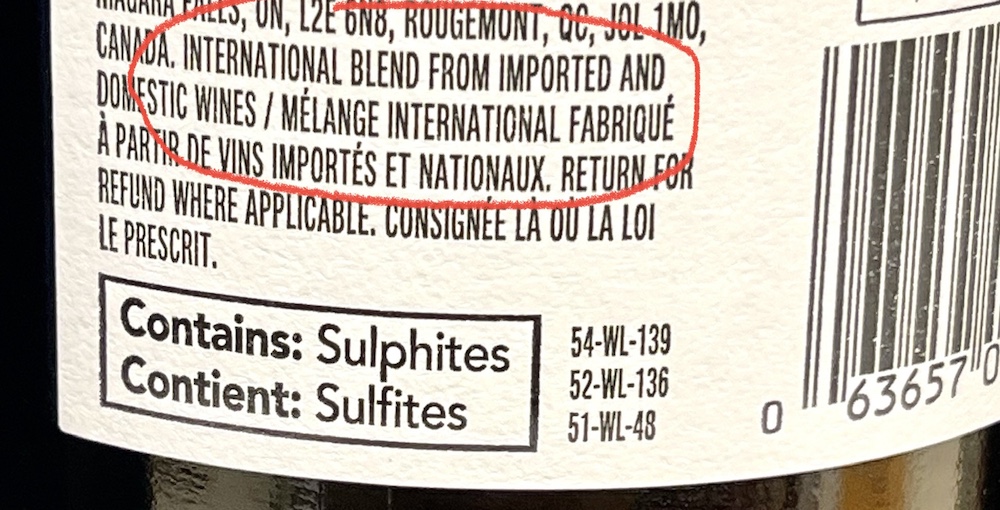

These International Domestic Blend (IDB) wines can contain a minimum of 25% Ontario grapes while 75% of the grapes are imported from Australia, Chile, Spain … wherever they can find the cheapest fruit. Sadly, these wines are made in greater volume than VQA wines and are sold under Canadian company labels with little information on them to inform the consumer on exactly what they are buying.

I don’t want to single out any one company making these wines in Niagara, so I am not naming my example here, but I came across an Instagram promoted story recently about one such IDB wine from a recognized brand. Aside from the fact that the wine was made from 75% imported grapes, and you would be hard-pressed to know that by looking at the bottle (it spells it out in tiny print buried on the back of the label that is an IDB wine). The bottle was being promoted with hashtags such as #ontariowine, #sippingontario, #vqawine, #niagarawine etc. All of which is not true.

It just points to the fact that after all the controversy with these wines, the large wine companies are still trying to confuse consumers into thinking that blended wines are authentic Ontario wines, which they are not. Yes, they fuel the industry. Yes, they employ Ontario workers. Yes, it helps growers prosper. But the constant presence of IDB wines, previously called Cellared In Canada, in LCBO stores is fuelling the dark side of the wine industry in Ontario.

I would like to think this working group would have addressed this in their report. At the very least they should agree to put targets on the production of these wines so that over time we can just make them go away. Let’s say 25% minimum Ontario grapes today, 50% minimum Ontario grapes in five years, 75% minimum in 10 years and 100% in 15 years. Would that be enough time for farmers to make the switch to growing quality, VQA-grade grapes so we can put an end to IDB wines? Or, at the very least, make them, sell them in their own stores, and market them under clearly defined separate labels and get rid of the entire IDB section at the LCBO.

While it’s difficult to get exact numbers on VQA vs. IDB wines, the latest data I have is from 2008:

• Imported wines have 58% of the market share of all wines sold in Ontario

• International Domestic Blends have a 32% market share

• VQA wines have a 10% market share

• The volume sold of domestic wine is 75% IDB and 25% VQA 54% of the Ontario grape crop goes into ICB wines, the rest into VQA wines

• According to the LCBO, 20 million litres of VQA wine are sold across the province, while 56 million litres of IDB wines are sold.

That, folks, is not good, at least for the vast majority of small to medium sized wineries that only make 100% VQA wines.

The Vision 2030 report

The Uncork Ontario report came on the heels of a 2030 Vision action plan from Ontario Craft Wineries, VQA Ontario, and Wine Growers Ontario. First reported on Wines in Niagara here, the report laid out the group’s plan for “building and nurturing a vibrant Ontario VQA wine industry by 2030.”

“Ontario’s opportunity is to leverage our history, to embrace our future, our climate.and the preference local and global consumers have for the types of wines we make here in Ontario, to increase sales and to gain market share over imported wines,” the report concluded. “To accomplish this, we will invest in and nurture our vibrant Ontario wine culture.”

Two foundational factors were identified as drivers for the industry’s evolution over the coming eight years:

• “First, we will be successful when the consumer is our singular focus, exceeding their wants and their needs.”

• “Second, we will re-create a unified industry voice to advocate for improved consumer and producer outcomes — with governments, with regulators and with our sales channel partners.”

These two VQA industry initiatives are the foundation that will support the Ontario wine industry’s success in “having a more engaged consumer, delivering increased sales and a more financially sustainable and successful VQA industry,” the report said.

One of the more ambitious goals of the Vision 2030 plan has to do with sales of VQA wine at Ontario’s booze monopoly, the LCBO, where right now the industry holds a tiny 7.7% market share and a 13% market share across all channels. “With the right support, by 2030 VQA’s share of the Ontario wine market will grow by over 20%,” the report said.

That giant leap forward in VQA wine sales at the LCBO in seven years caught the full attention of Southbrook Vineyards’ owner Bill Redelmeier. He was there for Vision 2000 and for Vision 2020 and said both of those reports were only “partially successful,” he said.

“We were trying to improve the quality of the wines. Check. We were trying to improve the visitor experience. Check. We were trying to become export-ready and competitive. Check. However, in each of those strategies, a key part was to increase the amount of Ontario VQA wine sold at the LCBO. We have certainly increased the amount of wine that we sell at our own retail stores, but we cannot seem to sell more wine at the only other retailer in Ontario — we’re still at less than 8% share. There’s no reason Ontario can’t do better, but only if the LCBO can be bothered to come to the table. Nevertheless, I am hopeful for Vision 2030.”

I reached out to Redelmeier (in photo below), whose organic farm winery was founded in Niagara-on-the-Lake in 1991 with an initial production of 2,000 cases crafted by veteran winemaker Derek Barnett, for some of his thoughts on the way forward for the Ontario Wine Industry. Redelmeier has been an important voice for 100% Ontario wines for over three decades. He has an analytic mind and is a student of how other jurisdictions navigate the complicated world of alcohol retailing.

Q&A with Bill Redelmeier

Wines In Niagara: You said in your newsletter earlier this year that you were happy to see the industry coming together to tackle the important issue of increasing market share for VQA wines in Ontario, but at the same time you lament the fact that not a lot has changed on that front since the Vision 2000 report. What gives you hope after learning about both the Vision 2030 report and the more recent Uncork Ontario report?

Bill Redelmeier: For years, the industry has been fractured into many groups: the GGO (Grape Growers of Ontario) vs the wineries, even though most wineries are growers. The WCO (Wine Country Ontario) vs Winery and Growers Alliance, vs the ultra-small who don’t want to join VQA vs VQA vs ICB. No one would talk, and without a united front, the government wouldn’t do anything to help. Each group was so jealous of the others getting ahead, nothing happened.

WIN: You place much of the blame for stunted growth in VQA sales squarely at the feet of the LCBO. Market share has held steady at under 8% market share at the province’s largest retailer for decades. Why has it never improved while B.C. has seen substantial growth?

Redelmeier: Without the united front, no one in the government took the chair and president of the LCBO aside and quietly said in their ear, “we really want you to purchase and sell more Ontario wine. We cannot write it down, but we would really be pleased.” No other wine producing jurisdiction sells that little, even B.C., which has much lower production than Ontario, sells more through the BCLDB (British Columbia Liquor Distribution Branch).

WIN: You said that one of the positive things in the Vision 2030 report, was the cooperation from the Grape Growers of Ontario, the Wine Growers of Ontario (the big wineries) and the Craft Wineries of Ontario (the small to medium wineries, VQA only) that all “seemed all to be singing from the same song sheet.” From where I sit as an observer, it seems that not all those associations have the same motivations. Is it possible for the craft wineries to work toward the same goals as the larger wineries, who rely heavily on blended (IDB) wines to drive sales?

Redelmeier: The voice of unity is the most important thing. In any negotiation you don’t get everything that you want. I don’t care about ICB, except when the LCBO markets and reports it as Ontario. PS: I love that the equivalent of ICB is sold in Quebec in dépanneurs: it means they don’t clutter up and confuse things at the SAQ (Quebec’s government booze monopoly).

WIN: I guess the toughest question that I have for you is this. How can the Ontario wine industry make the government stand up and take notice of all your legitimate concerns? It seems like every plan; every vision begins and dies in Niagara without anything ever happening at Queen’s Park. As you point out, “the local wine industry is protected and encouraged at almost every other place in the world. It is recognized as a driver of the tourism industry — around 15% of the GDP of both France and Italy is tourism, much of which centres on food and wine, and the largest tourist draw in the fourth largest economy in the world (California) is the Napa Valley. Even B.C. does a better job than Ontario with land values for vineyards at six times the rate than here.” But that message doesn’t seem to sink in at Queen’s Park.

Redelmeier: With the support of John Peller (president and CEO of Andrew Peller Ltd.), and the unified voice of everyone else, and the panic of the industry, we may be able to accomplish something. If we revert to bickering among ourselves, we are toast. Some wineries will survive by focussing on DTC (direct to consumers), but the taxes payable are ridiculous. When a small winery in California prices a wine in their retail at $30, they get to keep $30. Here, we get roughly $20.

WIN: Last question. I believe you have said that privatization might not be the answer to driving VQA sales in Ontario. I have always maintained that a private system or at least a co-existing system that allows full private enterprises to sell wines not controlled by the LCBO would be a catalyst to increased sales. Why do you feel it wouldn’t work in Ontario?

Redelmeier: The USA is a private system, but the three-tier system favours domestic producers. In Ohio, for example, the importer must mark-up wines by 30%, the distributor must mark-up by at least 30%, meaning that a wine that I want to export for $10 is offered to a retailer for $16.90. If I am an American winery, I can offer my wine to a distributor for $10, which will be offered to the retailer at $13, or I can offer it directly to a retailer at $10. Which would Total Wines buy?

Another problem that we have seen with bottle shops, for example, is that the system favours those wines whose prices are not ‘transparent.’ All Ontario winery prices are searchable online, which forces shops to keep markups down, whereas with consignment wine prices are opaque. This is the problem when the LCBO considers us as their major rivals rather than allies.

My suggestion is to break the LCBO into 3 pieces: LCBO importer, distributor, and retailer. Like Alberta, get rid of the functions that the board does not do well, like buying, warehousing and possibly retailing. Only charge producers for what they need:

Ontario Wineries don’t need an importer, and if I am selling directly to a resto, I don’t need a distributor. Imported wineries need an importer. If they want to sell through the LCBO, they would pay distributor and retailer. Restaurants don’t need a retailer.

This sounds more complicated than it is, but the reason for doing it this complicated way is to be able to say: If you don’t think that this is trade legal, we are just copying the U.S. If we are trade illegal, so are they.

Good article, but I’ve seen reports and routes to success more than once. There is a box of them beside my desk.

At a wine conference in NOTL a few years ago where Tony Aspler had a very good talk laying out how we get successful. He compared Niagara to BC which you reflected in this article. Nobody was happy Rick, we have a two faced double talking industry. The core growers who will over throw the GGO board if anyone moves away from the sweet profit point. These growers are hand in hand with the big wineries have a single voice, and the way things are is exactly the way they all want.

Niagara is tiny and has a huge local market, the fact quality wine growers are for the most part gone is telling. The fact that while the foot print of production is down production over all is way up. Why, grow unlimited amounts of fruit per acre. That was one of Tony’s suggestions, cap tonnage per acre to give quality.

I started growing in 1994 which had 550 actual growers and nothing but hope, today with multiple license per farm and wineries maybe there are 50 growers left who just grow.

Personally I feel we have to wait for the current batch of growers remaining to retire and create a vacuum of grapes before any meaningful changes will happen.

Ed, thanks for your comment. But what if we made it more worthwhile for growers to grow quality grapes at attractive prices and weaned off grapes destined for ICB wines over time, wouldn’t that be an option? I understand the attraction of planting grapes, letting tehm get to 8+ tonnes an acre and sending a mechanical harvester through the vineyard with no selection at all. No labour, just let it grow. But what if growers knew their wines are going into 100% VQA wine? Over time, that might be a powerful motivator, no? — Rick

One other reason sales are stagnant is the exposure of VQA wines in restaurants. In Nova Scotia every restaurant has to have Nova Scotia wine that pairs with seafood. People see more Ontario wines( no 20 Bees) on menus the likelihood they’ll be more interested in VQA wines.

While I really like the name of that Deloitte report (it almost sounds like it would make a good Twitter handle), I have to say that I’ve seen diminishing support for Ontario wines in most of the LCBO stores I visit. The dedicated floor space is dwindling, and the confusion over what’s ICB vs VQA wines almost seems intentionally blurry. Sad.

I got for all my fruit a significant bonuses, but in the last few years cost skyrocketed while the price I could get are indirectly capped because of the LCBO. I poured a lot of heart and soul into growing high quality grapes. But my wineries can’t get prices that would be needed to make me profitable. They do in BC.

I’ll make the prediction that once the field of growers are very thin their protection from the GGO will be gone. Who needs a multi million dollar organization for 20 business? Then the growers will be at the wineries whims.

Interesting input & views.

Support is -strongly- needed, both at the provincial and the federal levels, the rapidly evolving Canadian wine industry deserves it.

Opposite forces do occur in many regions across the world. Canada wines and regions need to overpass it and to unite.

Do you know if the reports -Uncork Ontario and Vision 2030- are accessible somewhere?

Best wishes

It is incredible what the Niagara and Ontario wine industries have accomplished with so little support from and so many obstacles (mainly outrageous taxation) from the provincial and federal governments. The 1989 Inniskillin Vidal Icewine beat the world and won the 1991 Vinexpo Grand Prix d’Honneur in Bordeaux. The 2005 Le Clos Jordanne Claystone Terrace Vineyard Chardonnay beat the world and won the 2009 Judgement of Montreal. Imagine what could be accomplished if the powers that be actually believed in Niagara wines and gave them a level playing field. The producers and growers aren’t demanding preferential treatment, they just want equal treatment with the imported wines that, in comparison, barely contribute to our domestic economy. No other major quality wine producing region anywhere in the world sees their local wines outsold like Ontario does. Why do we permit and tolerate it? I can’t see the French, Spanish, Italians, Americans, Australians, New Zealanders, Argentinians, Chileans, Germans, Portuguese, Chinese, or people of any country with both quality wine production and any semblance of regional and national pride allowing Canadian wines to outsell their own in their domestic markets. So why do we permit them to outsell our talented, local, hardworking grape growers and winemakers in Ontario? Why do our provincial and federal governments, so quick to endorse and support our domestic teams, athletes, artists, musicians, entrepreneurs, and other equally talented persons, turn their backs on some of the most talented and hardworking individuals toiling in our wineries, working the winery tasting rooms, working on the bottling lines, working events late into nights and weekends, delivering products through terrible traffic, working the soils, tending the vines, spreading fertilizer, delivering sprays, fighting infestations, investing their life savings and more into their businesses selling top quality locally grown grapes and wines, and taking care of the dozens of other tasks behind the scenes to ensure that top quality VQA wines reach their loyal followers across the region and beyond. As Rick outlines in his article, it is painfully obvious to all readers that all Ontarions and Canadians stand to benefit from all levels of government treating local growers and producers equally with imported products. Why not support our neighbours, friends, and coworkers? Why don’t the politicians support those who elected them, or at least those who stand to benefit from them supporting local? We make fine wine here in Niagara and in Ontario (shout out to Prince Edward County, Lake Erie Northshore and Pelee Island, and to the Emerging Regions like the Huron Shores and Holland Marsh, and the pioneers in all areas). If the powers that be could only permit these locally grown products to compete fairly with imported wines, we all stand to win. What is stopping them? What is holding them back? As Rick outlines, scale back the international blending (that no serious quality wine region would wilfully permit), scale back the taxation that treats domestic products with the same taxes as imports (tariffs on domestic products!?!), and give our local products a chance to thrive and benefit us all. Then watch as our market grows, our business grows, our reputation grows, and our collective quality of life grows thanks to the additional income generated by equal treatment of locally produced wines. Only fools would obstruct, argue against, stand in the way of, and try to prevent the universal benefit of supporting our local producers, permitting them to grow and thrive, supporting the industry and beyond with their success that only government red tape and antiquated opinions are holding back. Just give our wineries equal footing equal endorsement, and a fighting chance, and watch what we can accomplish.

Thanks for this, Dan. Well said. I also posted your comment to my Facebook page so more people can see it.