By Rick VanSickle

Nearly seven years ago, an enthusiastic group of Niagara Riesling lovers — most of them winemakers — gathered to taste a wide range of well-aged Rieslings from Ontario.

Note: We open some fascinating old Niagara wines from Chateau des Charmes, Cave Spring Cellars and Charles Baker at the end of this report.

The tasters included Niagara winemakers and others in the industry, who all brought some of their oldest bottles of Riesling from their own cellars to compare against newer bottles to see how they had matured over time.

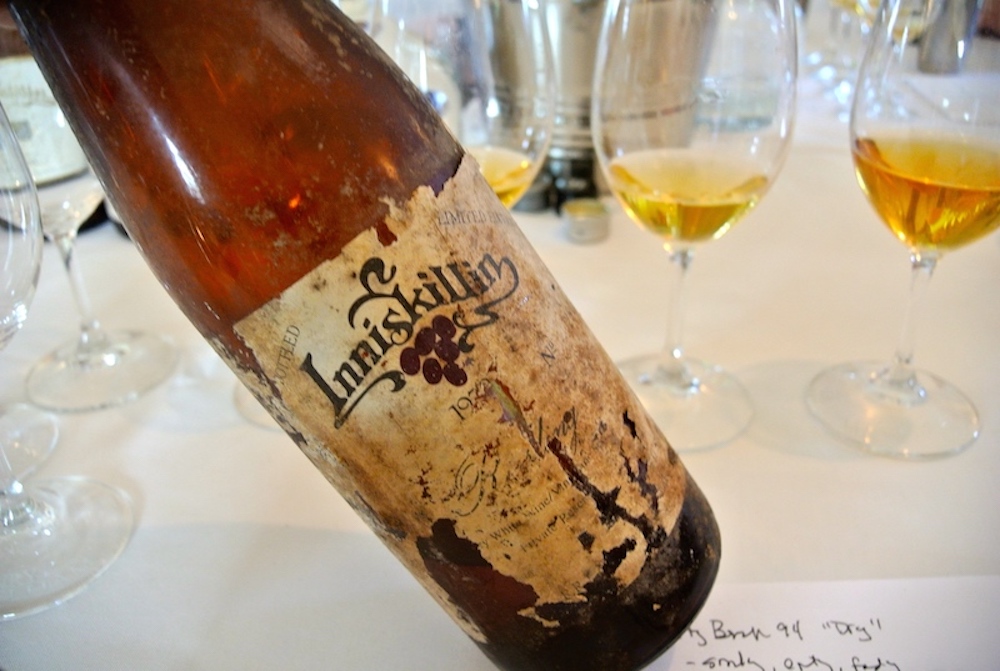

The oldest bottle at that tasting was an Inniskillin Riesling 1979 and the rest, for the most part, were from the 1980s and 1990s with a few “reference” Rieslings for perspective. It should be noted that the modern era of winemaking in Ontario only began in 1974 when Inniskillin was granted the first new winery licence since 1916 Prohibition. So, tasting old Rieslings from 1979 on up was an incredible experience likely not to be repeated.

Many of the wines that were brought to the tasting pre-dated the Vintners Quality Alliance, established in 1988 and created to set out geographic appellations and introduce strict production standards that became law in 1999. So, it’s safe to say that the older Rieslings of the 1980s and 1990s that we tasted were experimental as winemakers were still trying to figure out what worked best in the harsh climate of Ontario. As J.L. Groux, Stratus winemaker and former Trius winemaker, said when asked how his 1991 and 1998 Trius Rieslings survived the years in such good shape he had a quick answer: “We had no idea what we were doing back then.”

If there were lessons from the past, winemakers were so focused on making the best wines they could from the new push toward vinifera grapes that we may never know what those lesson were.

But perhaps Vineland Estates winemaker Brian Schmidt said it best when asked about the tasting: “This was a such a great opportunity for us all. To listen and participate in a discussion about our history, the clear and not so clear memories of vintages past, the powdery mildew year, the black rot year, the hot years, the rainy years, the great years, the not-so-great years. We learn from these moments … we gain insight into future vintages. This was absolutely amazing.”

The most fascinating aspect of the tasting for me was the randomness of what survived through the years. There was no pattern of evidence as to why one wine would evolve so graciously while others did not. It seemingly had little to do with residual sugar (some dry wines were unbelievably fresh for their age). Acidity can be a factor, but let’s face it, acid has never been a problem in Niagara.

Winemaking may have contributed to longevity but some of the veterans around the table said everyone was just trying different things to make up for the various conditions thrown at them, be it vineyard disease, wet conditions or cool/hot vintages.

The bigger takeaway for the group, was the fact that Niagara wines have the DNA to age with the best wines in the world. While the above was a Riesling retrospective, a follow up tasting a year or so later would feature old Niagara reds to equally thrilling results.

There aren’t a lot of those cool older bottles of Niagara wine hanging around anymore. There wasn’t a culture of cellaring local wines and wineries didn’t put many away for future tastings. It was risky, there was no history to go on and no one was sure if a) they would cellar and b) would they be worth drinking.

Wine drinkers are much savvier now, they understand the concept of cellaring, and those who have a acquired a taste for older wines, know what to buy and how long (approximately) to hold them. I am starting to see some Niagara wineries even holding back some of their best bottles for a late release. Stratus has a program where it releases some of its well-aged treasures to consumers (I missed out on a recent release of the 2007 Stratus Red) a few times a year. Vineland Estates always has back vintages on the shelves at its retail store, and I see more and more wineries holding back vintages that are likely in need of more time to be better appreciated.

Cellaring wine is no longer solely for the wealthy, and no longer reserved for the bottles that cost hundreds and hundreds of dollars. I think the Riesling tasting above will attest to that — very few of those bottles cost more than $15 at the time, and really haven’t risen in price like many of their estate’s red wines.

My social media feed these days is bursting with posts showing older bottles of Niagara wine being opened and enjoyed. Two of my favourite follows on Instagram — Andre Proulx (@andrewinereview) and Miroki Tong (@9ouncesplease) — focus on inexpensive to mid-range wines to put away and offer valuable insight to budding millennial wine lovers on how and what to cellar. And they do it by tasting the wines and offering their opinions on what works, what doesn’t and why.

It was their segment, that they call “Cellar It,” that prompted me to respond a while back with a long-winded answer to their question on what comes first when you are looking for wines to cellar: Vintage, price or variety.

I responded, that for me, it’s variety, vintage and then price. If there must be a hierarchy for cellaring, I believe it goes in that order. If you see a currently released Hunter Valley Semillon on the shelf, you need to cellar that sucker no matter the price or vintage. It is just so much better with age. Conversely, not many Gamays, regardless of vintage/price, benefit from cellaring (though there are currently more structured Gamays being crafted, especially right here in Niagara, that might make me change my mind).

All Bordeaux reds need cellaring regardless of price, vintage and variety dominance. But a caveat there … vintage plays a huge role. There are some bad vintages in Bordeaux that you just wouldn’t buy at any price and no cellaring in the world will save them. In fact, they get worse. Riesling almost universally (regardless of price and vintage) benefits from cellaring, but few people realize it. No one is cellaring Pinot Grigio (I hope), and no one cares about the vintage; it is what it is and if you have any in your cellar, drink up … and enjoy!

I’ve never met a Niagara Bordeaux variety blend that didn’t need at least some cellar time to improve, but vintage does play a role as does price. No amount of cellaring will cure green (unripe) notes and don’t expect a $12 Niagara red blend to improve over 10 or 20 years in the cellar, but a little time can help that red go from ho-hum to giddy up. And the better ones? I can see some going 10-20 years and maybe beyond. Chardonnay? I generally like to cellar them even if it’s only a couple of years, some a little longer. They reach a peak and fall off the cliff quickly (I have some in my cellar like that right now, dammit). There are always exceptions to the rule (Burgundy, Prince Edward County and some Niagara examples included).

Rosé? Buy them, drink them. Cabernet Franc? Cellar them, but not for as long as your more structured reds. Merlot? Cellar them, at least for a bit. Sauvignon Blanc? Drink. So, my rather disjointed theory is variety over vintage over price.

Let’s talk price a bit. You can cellar on a budget. The 2020 vintage in Niagara will be a good starting point. The big reds, even at the entry level, will all benefit from some aging. Inexpensive Rieslings are a fine example of cellar candidates from Niagara and beyond, while the single-vineyard Bench examples can cellar up to 20 years in good years.

Once that acidity settles down wonderful things happen. You can even find fantastic Bordeaux (vintage matters a bit more here) at bargain prices that you can cellar for a long time and improve them. Pinot Noir is complicated and tricky, and maybe more driven by producer and region (in Niagara, cooler vintages cellar better than warm vintages).

That was a long dissertation on a simple question that was posed on IG, but probably not detailed enough to try and explain the intangibles of cellaring old wines and appreciating them. I happen to love my wines well aged, and even find joy in the ones that are obviously over the hill and of no appeal to most wine lovers. It’s a fault, really. I have wines kicking around from Niagara, Bordeaux, California, Italy and other places that should have been consumed years ago. Some of them I just can’t bear to open, others waiting for the right moment.

I took the opportunity for this report to open three such wines this week with distinctly different styles with backups ready if any of them completely disappointed. To my surprise, all three — the oldest a 1988 late harvest Riesling, and the newest a 2010 Riesling — were in fairly good shape, with the Riesling from Charles Baker just past prime time, and the other one past peak, but still of interest, at least to my palate. Let’s start with the Riesling.

Charles Baker Ivan Vineyard Riesling 2010 ($27 at the time, 91 points when scored in 2011) — 2010 was in inaugural vintage for the Ivan Vineyard Riesling, located in Vineland in the Twenty Mile Bench appellation. This 12-acre mixed high-density planting includes a pristine single acre of Riesling planted late in the 20th century. Planted in rows running south to north on a clay/limestone base, the vineyard benefits from the updrafts of Lake Ontario while benefiting from all the inland warmth of the growing season. It is owned by grower Bob Nedelko. Baker said he cropped the Riesling perhaps a little too aggressively and ended up picking a measly 1.3 tonnes per acre. After an intense sort at the winery, the free-run juice was kept separate and ended up as the 2010 Ivan Riesling. It is a truly different expression of CB’s key Picone Vineyard Riesling, and not just because of the hot vintage of that season. It leads the Baker “style” down a new path, one that is always a unique expression of the vineyard from where it comes.

In my review at the time, I noted that the nose revealed sharp lemon-lime and grapefruit citrus, soft peach, orange zest and an alluring hint of stony minerality. It was very dry, with less acidity than previous CBs, on the palate and the rich flavours of lime and grapefruit lifted by an interesting note of ginger on the finish. Twelve years later, the wine showed a deep golden colour in the glass and had a savoury nose of lemon tart, emerging petrol, grapefruit pith, peach preserve, ginger and wet stones. It is rich and fleshy, complex and profoundly altered from its original self on the palate. It opens up to a waxy/lanolin note and then a melange of mulled peaches, citrus marmalade, canned pears, ginger and more pronounced petrol and mineral notes. It’s a touch soft on the finish, as are a lot of 2010 Niagara wines, but still an interesting wine to judge against a new vintage.

Cave Spring Indian Summer Riesling 1988 (now called Cave Spring Indian Summer Select Late Harvest Riesling and a popular seller at the LCBO for $25 for a 375 mL bottle) — The Indian Summer late harvest wine in 1988 was picked at 24.7 Brix and finished with 55 g/l of residual sugar, somewhat drier than the style is now made. I was frankly surprised this held as well as it did. The ullage was low, and the cork pushed through the neck into the bottle when I attempted to free it, so it had to be filtered and decanted. But there was no leakage at all. It showed a deep caramel colour in the glass and had a rich and complex nose of dried apricots, sultana raisins, papaya, guava and sweet canned pineapple. The tertiary flavours were on full display — caramel toffee, mulled peaches, butter tart with raisins, compoted tropical fruits, dry honey and brown sugar with a lovely freshness on the finish. Really interesting wine all these years later.

Chateau des Charmes Paul Bosc Vineyard Cabernet Sauvignon 1994 (in today’s prices about $35, back then around $18) — Paul Bosc is one of Niagara’s most important pioneers, especially when it comes to planting vinifera varieties and making these bolder style red wines. His namesake vineyard is one of the few vineyards in the region with southern-facing slopes. It was planted in 1983 and 1984 with the first harvest in 1988. The cork appeared like it might pose a problem considering the layer of a dust-like substance under the cap, but it flew off and exposed a relatively sound cork. I used the trusty Durand corkscrew to liberate the cork and it came out in one piece. It had a bit of an odd odour at first of barnyard and forest floor, but then turned woodsy with a melange of red berries, kirsch, wild blackberries, integrated spice and oak notes with earthy/savoury undertones. It was quite pleasant on the palate with fully integrated, resolved tannins yet still vibrant and mature red berries, minty herbs, earthy accents and the oak all but consumed by the fruit. Incredibly (or not) there was still plenty of lively acidity on the finish. Yes, should have been consumed years ago, but fascinating to taste this Niagara red 28 years after the fruit was harvested.

THANKS FOR THE SHOUTOUT! This is pretty cool. I’m still at the enjoying my wines young(ish) phase of my wine journey – but as you start to horde wine things get forgotten and older… and then you’re just like… I guess I’ve already started this.

My experience as well. I loved wines in their youth, but started tucking a few at a time in cubby holes and eventually into cellars we built in various homes and then BOOM! I was on a new path of aging the majority of our wines at least for some time to soften the acids and tame the tannins. Eventually your palate craves the flavours age brings. You also learn by your mistakes … I originally cellared quite a bit of Shiraz (it was a phase!) from Australia and almost all whites from Alsace. That didn’t turn out too well.