By Rick VanSickle

Riding high atop a super-sized ERO Grapeliner 7175 XV harvester, there’s that Leonardo DiCaprio moment where I just want to shout: “I’m the king of the world!”

Also in this report, Grimsby Hillside Vineyard’s Paul Franciosa makes a case for the premiumization of Niagara winemaking.

The 360-degree view, 20 feet above the vines on a blue-sky harvest day in Niagara is a feeling of pure bliss as the hulking harvester straddles a row of ripe Gamay grapes at the Huebel Grapes Estates home vineyard in Niagara-on-the-Lake and makes quick work of stripping the vines of their precious bounty. The mechanical harvester is shockingly efficient and can pick, destem, and sort grapes on board before offloading to vats enroute to the press for processing.

I’m riding shotgun with pilot Liam Barrett (above, left), and Jessica Oppenlaneder Solanki is outside the cab behind us as we zip up and down the rows of Gamay. I’ve witnessed countless harvests in Niagara and other wine regions around the world, but never from a perspective such as this. Today was a good day.

The Gamay looks gorgeous, as do most other varieties picked so far in Niagara, despite a miserable, wet August. A warm, relatively dry fall turned what could have been a troubling 2023 harvest into a more classic vintage.

Matthias Oppenlaender, who established Huebel Grapes Estates in 1984 with the Huebel family with the goal of growing quality vinifera grapes for quality wine production in Niagara, has diversified over the years. The family has purchased more vineyards and established its own virtual brand called Liebling Wines led by the next generation of Oppenlaenders, Alison and Jessica along with brothers Aaron, Michael, and Danny (all above in a family photo taken last week). The mission at Liebling is to showcase the single vineyards the family own and the vines they grow.

Touring the family’s Creek Road Vineyard with Alison and Jessica (above) on this day of harvest, you can feel the pride in the family’s latest endeavour in winemaking. The plump Gamay grapes that will become part of the 2023 vintage of Liebling wines are ready for picking and two special rows have been set aside for the project. Along with Gamay, Liebling also crafts a Riesling and Sauvignon Blanc in the portfolio with a Cabernet Franc coming in 2024.

It’s exciting to see the younger generation take the reins in a business that is increasingly feeling challenges, not the least of which is a looming surplus of grapes in Niagara that is sending shockwaves across the region for growers.

Depending on who you talk to, there are between 2,000 and 4,000 tonnes of Niagara grapes worth millions of dollars sitting on the vine unsold. If buyers aren’t found, and found soon, they will be cut to the ground, left to rot. What’s even more shocking is the fact that the surplus comes after a shortfall just a vintage ago.

Wines in Niagara did its own math of grapes for sale as advertised on the Grape Growers of Ontario (GGO) website just for the month of September. The numbers added up to 2,280 tonnes of grapes listed with Riesling leading the way (321 tonnes), Vidal next (302 tonnes), Chardonnay (200 tonnes), Merlot (185 tonnes), Cabernet Franc (184 tonnes), and Cabernet Sauvignon (154 tonnes). The grapes with the least number of grapes for sale were Pinot Noir (with 12 tonnes), Sauvignon Blanc (13 tonnes), and Gamay and Syrah (both with 35 tonnes). Wines in Niagara did not include the various hybrid gapes for sale (200+ tonnes) in the calculations.

For Huebel and the Oppenlaender family, a well-run, successful business with most of its 400 acres of grapes contracted to the larger wine companies in Ontario, they, too, have felt the squeeze on grapes. “It does impact our business as well,” said Matthias Oppenlaender, mostly with some of the company’s rented vineyard properties. But he fears if things don’t change quickly, some contracts might not get renewed in the future.

The pending surplus, which the GGO says is just over 2,000 tonnes for sale according to its own numbers, sparked a poignant post by Rob Condotta (above), the farm manager at Honsberger Estate Winery. The Honsberger family has been farming their land since 1811. The current sixth generation has made the most profound changes in the history of the property. In 2002, Barbara Honsberger Condotta and husband Rob Condotta ripped out the cherry trees to plant Cabernet Franc and apple trees were removed to plant vinifera grapes. For a while, some of that fruit was sold to other wineries but the family was eventually convinced to take the next step in their evolution and start their own label under the family name using grapes from 11 acres under vine.

“As a grape grower, I can’t help but wonder where the industry is going,” Condotta wrote. “Does our government really get it? Are they aware of the current situation? I don’t think so.” Condotta fears the government just doesn’t understand the impact its crippling taxes, fees and levies have on the grower community. “Yes, everyone drives by and sees all the beautiful vineyards with fruit hanging and think life is just beautiful,” he wrote. “And for some, it’s OK, but for many right now, they are scratching their heads. At present there are more than 3,000 tonnes of grapes that don’t have homes. This represents over $4.5 million in sales to farmers at an average price. This, in turn, represents a loss of wine volume being produced, which works out to approximately 2.5 million litres of wine.” Condotta cautioned that those numbers are approximate and depend on juice volume.

“I can’t figure it out. Is it market decline? A possible glitch currently in consumption? Or is it the fact that we can’t compete with the LCBO,” he continued. “What gives? Are we growing the right product, the right varietals? Is the marketing board informing us correctly? I don’t have the answer, but this is the first time I have ever seen so many grapes on the market with no home, no buyer.”

Condotta doesn’t believe the Ford government has a grasp on just what is unfolding in wine country. He warns that if Premier Doug Ford, in his quest to make beer and wine more accessible for consumers, might just end up hurting the Ontario wine industry. “If he even thinks privatization of wine and beer in convenience stores, the grower will be in big (trouble) and the local producers that purchase all these grapes normally will cut even more as the cheapest of imported wines become more available in stores all over, with help from the LCBO,” he wrote.

“I fear we are in a downturn, and I think this is just the start of the market declining rapidly. I feel bad for those farmers that have injected so many dollars into a tough year and end up on the hook with all these grapes and no revenue. Time will tell, I guess. Hopefully these farmers sell their grapes this year.”

The GGO, which represents grape growers farming more than 18,000 acres of vineyards, and sets the price of grapes, is deeply concerned over the surplus, the largest glut since 2008 when 8,000 tonnes went unsold.

Wines in Niagara interviewed GGO CEO Debbie Zimmerman (above), chair and former Grape King Matthias Oppenlaender, and market analyst Mary Jane Combe over Zoom last Friday. The problems and the solutions are complicated and there are no easy fixes. The Ontario wine industry is at a crossroads, with declining sales, changing consumer habits and the expanding zero-alcohol market, and upcoming decisions being made at Queen’s Park by Doug Ford and his government is the wild card that will either help or hinder growth for grape growers and estate wineries.

“The future seems uncertain,” said a frustrated Zimmerman. She points to market share at the LCBO stuck at 7.3% for Ontario VQA wines, with the number only rising to 12.1% overall for all VQA wine sales. The rest of the market is imports at 55.6% and IDB (International Domestic Blends, which can contain as little as 25% Ontario grapes) wines at 32.3%.

Zimmerman and Oppenlaender feel that the “uncertainty” about where the market is heading is the main factor why wineries aren’t purchasing more grapes for their productions, creating the surplus.

As one grower told me, and who asked not to be identified: “Sales are down but that is not the full reason for the surplus. The feds and province had to ‘rethink’ their programs (due to the world trade challenge) that ‘encouraged’ the blenders (the larger Ontario wine companies such as Peller and Arterra) to put 100% Ontario product in the IDB bottles,” he said. “These rethinks have taken the benefit away and now the blenders are going back to 25/75 (25% Ontario, 75% foreign) blends. This has put a lot of grapes in surplus with many more coming as grape supply contracts mature and are not renewed. I believe the last time there were 5,000-tonne surpluses the province and the federal government came up with programs to encourage purchases and it was great for the industry for 11 years.”

A consortium of wine industry associations recently joined forces to lobby the Ontario government to make profound changes to right the ship for wineries and growers alike. To achieve that, many factors would have to be enacted for the strategy to ever be successful. Some of key takeaways:

• The tax burden on Ontario wine is too high: Ontario’s wine industry is the most heavily taxed in the world. Ontario’s wine producers also don’t have direct delivery privileges in their own markets. What’s more, leading wine jurisdictions from around the world receive billions of dollars in subsidies

• Retail expansion must be done right or else it threatens the future of Ontario wine and further supports heavily subsidized, foreign wineries: The GDP impact of a private retail model on domestic wine sales and tourism was estimated to be a negative $760M in GDP at year 10 after retail expansion, before indirect and induced effects

• The LCBO holds the future of the domestic wine industry in its hands. It must make the domestic industry its priority—or stunt its growth: The market share for Ontario wines has remained relatively flat over the last 20 years. A major contributing factor is the lack of representation on LCBO shelves. If the Ontario wine’s market share by sales (33%) increased to that of B.C.’s market share (47%), it could provide $800 million in additional GDP over a ten-year period to Ontario’s economy

Zimmerman and Oppenlaender also point to other factors that need to be addressed.

• A 6.1% “sin” tax levied on every bottle of VQA wine, but not on imported wines, sold in the province must be eliminated permanently

• The LCBO can do much more for Ontario wineries. “Right now, Ontario wines are treated like an import,” said Zimmerman

• Reform the way Ontario wines are sold in Ontario with a model based on the British Columbia retail system, with a permanent and uncapped VQA and 100% Ontario wine support program

That last point is critical, said Zimmerman. Ontario wines are not imported products and should not be treated as such, she said.

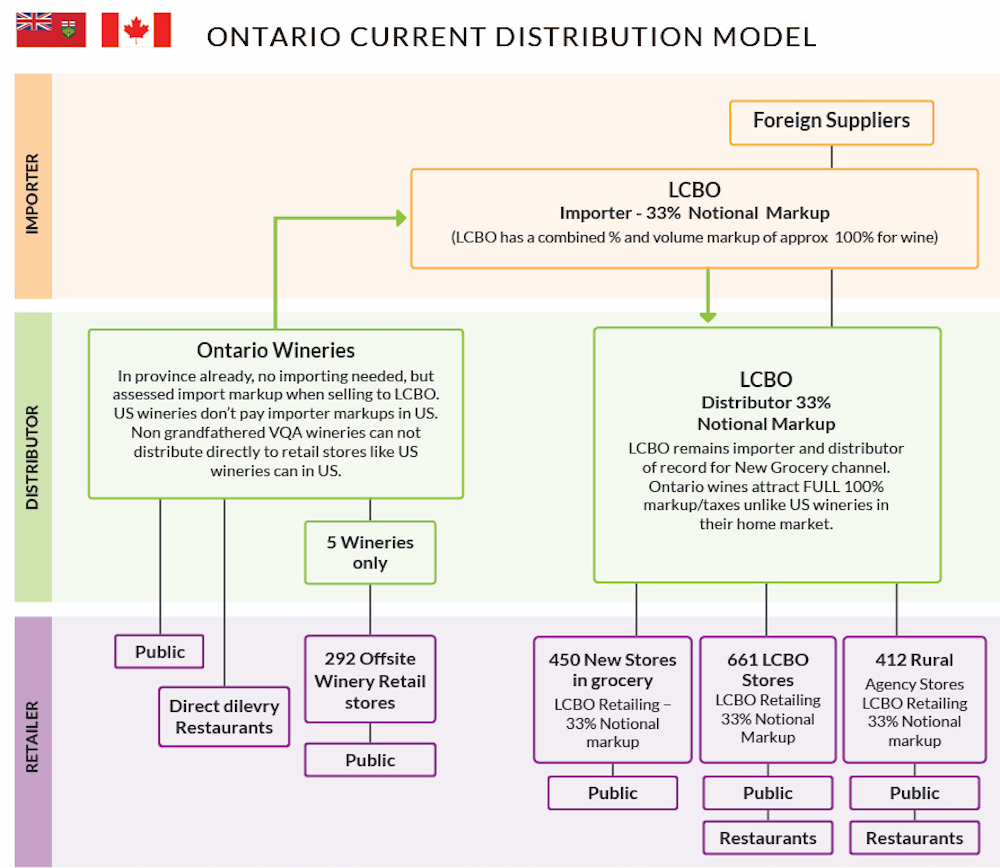

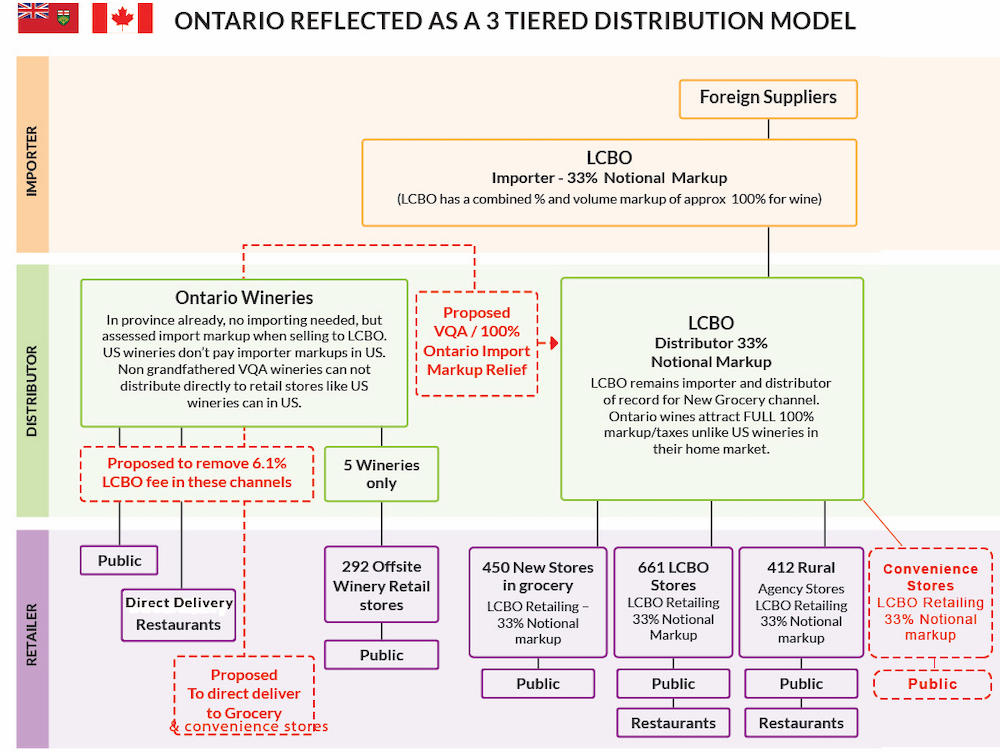

A three-tier distribution system — similar to what is used in B.C. — is an effective policy change that reflects the way domestic wines are treated in other wine-producing regions, including the United States where domestic wines do not face an importer markup. This model recognizes VQA and 100% Ontario wines as the local products they are by removing them from the notional cost of importing, saving them 35% of the markup they currently pay to the LCBO.

This move can replace the VQA Support Program (current cost $7.5 million) with an uncapped and permanent market-based structure that will improve margins for wineries, encourage investment in their business and create new pathways to expanded retail channels for 100% Ontario wines — including a more diverse selection of 100% Ontario wines on the shelves of the LCBO.

It will also remove a disincentive for some of Ontario’s smallest wineries to participate in LCBO programs targeted at producers who have smaller volume. By removing the additional 35% markup the LCBO takes as an “importer” on domestically produced wine, more small wineries will benefit from participating in existing LCBO programs and the new retail channels.

In the short term, Zimmerman and Oppenlaender know the GGO must be better communicators with grape growers. Zimmerman said the organization is “working on a varietal plan that will help guide the future” for growers. “We want to make sure we’re planting the right varietals. We need to fix the market for the long term.”

The GGO has also floated the idea to both B.C., which has a shortfall of grapes, and Nova Scotia to see if the surplus of Ontario grapes can benefit them and help Ontario growers at the same time. That solution comes with its own challenges, but every avenue is being explored to prevent as few grapes as they can from rotting on the ground.

“We’re still looking at things we could do,” Oppenlaender said, but one thing is certain: “Failure is not an option.”

One grower’s perspective

on what the future looks like

Wines in Niagara reached out to Paul Franciosa (above), who along with his brother Frank, own the Grimsby Hillside vineyard, a property steeped in history going back 150 years. Under new ownership, the Franciosa brothers have vowed to honour the legacy of their patriarch, Lou Franciosa, who dared to dream, dared to follow his path as a would-be grape grower, amateur winemaker, and lover of wine in retirement. His intent was to build something special that would carry on for generations. Lou Franciosa died of pancreatic cancer in 2006 at age 59, only four years after the vineyard was purchased and much of the planting already underway. With replanting and a desire to grow top-quality grapes, Grimsby Hillside has quickly built a reputation for growing top-shelf grapes being made by some of the best wineries in the Niagara. These are Paul Franciosa’s thoughts on what the future looks like in his own words.

By Paul Franciosa

We came in to 2023 with high expectations, expecting our fruit production to be expanded significantly from historic low production of 67 tonnes last year (compared to a 15-year average of 190 tonnes). A combination of recently planted vines coming online and vines increasing production after 2021/22 winter damage had us optimistic about the season. Early season expressions of interest were quite robust, but as the season moved along, we noticed some customers became increasingly hesitant to commit on volumes. The messaging we heard varied from “we have a lot of 2021 wine to sell still” to “we’re concerned about a possible recession” to “our home vineyards/longer standing grower relationships are producing at heavier than expected tonnages.” And of course, hanging over the whole industry is the global theme of reduced consumer demand for wine.

Reading stories about France paying wineries and growers to convert wine to hand sanitizer and pull (out) tens of thousands of acres of grapevines, and Australia and Spain and Italy facing similar surplus issues obviously gives a lot of people reason for pause.

Winemaking is a long-term game — grapes are purchased and turned into wine that might not be sold for 1-3 years down the road — and grape growing is even longer term. We’re trying to anticipate what the market will be 10-30 years forward when we’re making investments in new plantings. Demographic trends in many markets are changing — fewer younger people — and among younger people, fewer are drinking wine.

In their annual wine industry report for 2023, Silicon Valley Bank reported that the only age cohort with growing consumption was adults over 60 — all other age categories are shrinking their consumption. They reported 35% of adults between ages 21-29 drink alcohol but not wine. But it’s not just a trend for younger consumers: only 28% of adults between 50 and 59 drink wine.

But despite these challenging background forces, it appears that globally, the wine market is segmenting into higher end, super premium wines, which appear to have more demand than ever (and correspondingly higher prices) and everything else, which is competing for a smaller pool of consumer attention and dollars. We’ve been fortunate that many of our customers operate in the premium segment and have exciting and growing brands, and their customer bases are educated about wine, engaged and loyal. That helps buffer them and, by extension, us from some volatility in broader market trends. But we’re not fully insulated.

We have seen customers pulling back purchases, so we have had to adapt, and we’ve been able to bring in some new customers, who we couldn’t accommodate last year, to take on allocations.

We have a few of Cabernet Sauvignon and Riesling tonnes we’re still trying to find the right customer for — someone who is quality focused and produces premium quality wines, who wants to partner with a grower using responsible land stewardship and viticultural practices, who has a willingness and ability to pay premium prices for what we believe are premium quality grapes, and who treats us honestly and fairly in their business dealings, but we think they’re out there and we’re pretty confident all our grapes will find good homes this year.

We also recognize there’s a lot of new plantings that have gone into the ground in Niagara — especially of certain varieties like Cabernet Franc — and ultimately the question will be whether wineries can produce exciting wines and engage with their customers in a way that allows them to buck the trend of decreasing consumption broadly. From our perspective, our task is to focus on growing the best quality grapes we can to support winemakers who are looking to push the limits of quality in Niagara. If we do that well, we’re pretty confident our customers will be able to continue making wines that excite and engage consumers and can hopefully find a growing audience locally and internationally.

The Ontario Ford government … no economic business sense. It’s only a money grab as the have done the same thing over and over again now with cannabis as well. Living in the heart of wine country I am discussed and very upset with this government.

As a grower of grapes on a farm in niagara for all of my life. 7 the generation on the land .This disaster is the worst I have seen.All ready on my farm have removed 30 tonne from the surplus list of the grape grower of ontario web site because they are past harvestable quality and 20 tonne of vidal are headed the same way.

Douglas, That is very sad to read that. Hopefully the government will fix this terrible situation soon.